“The dynamic in developing countries is so different… protection gaps are much wider and penetration rates are much lower”.

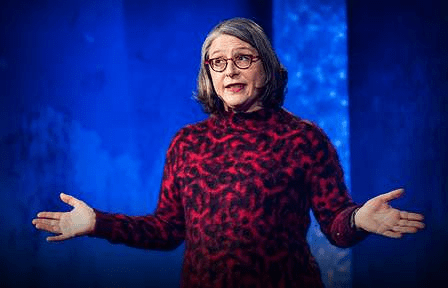

Author and strategist Michele Wucker coined the term “gray rhino” for obvious, probable, impactful risks, which we are surprisingly likely but not condemned to neglect. She is the author of four books including the global bestseller THE GRAY RHINO: How to Recognize and Act on the Obvious Dangers We Ignore. The metaphor has moved markets, shaped financial policies, and made headlines around the world. It helped to frame the ignored warnings ahead of the COVID-19 pandemic and inspired the lyrics of the hit pandemic pop single “Blue & Grey” by the mega-band BTS, about depression as a gray rhino. Michele’s 2019 TED Talk has attracted over two million views.

Michele is founder of the Chicago-based strategy firm Gray Rhino & Company. She has been honored as a Young Global Leader of the World Economic Forum and a Guggenheim Fellow. She has held leadership positions at The Chicago Council on Global Affairs; the World Policy Institute; and International Financing Review. Her writing has appeared in publications around the world including The Economist, The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Wall Street Journal. A much sought-after media commentator.

Startling observations

Michele’s recent observations on insurance in The Gray Rhino Wrangler are startling. Appearing under the head of ‘Insurance and Real Estate’, these are precisely the gray rhinos hurtling towards insurers:

- Insurers have been worried for some time about whether they are sufficiently capitalized to withstand claims related to climate disasters from flood to fire and drought. The answer has become increasingly clear: they are not.

- Year after year of record insurance payouts finally prompted insurers to withdraw en masse from the most climate-vulnerable areas.

- The insurance industry is now exploring new financing models and public-private partnerships even as it continues to revisit climate risk pricing.

- The climate challenge will make it increasingly difficult to ignore gaps in risk pricing whether in insurance, real estate, financial markets, agriculture. It also will increase pressure for policy change, particularly the reduction of fossil fuel subsidies – which continue to surpass government support for renewables.

- This will have growing implications for real estate as owners are priced out of their homes by the high costs of insuring them – though for some, it appears that the ability to self-insure and shrug off the possibility of catastrophic flood and wind damage is a status symbol.

- Water scarcity is threatening cities and homes in arid areas, while an overabundance of water is flooding other communities.

- Record insurance payouts as a result of extreme weather have caused a stampede of insurance companies away from the most climate – vulnerable areas and astronomical price increases in places where they remain. The implications for real estate prices and municipal budgets (which rely heavily on property taxes) are stark.

- This will compound the financial strain on municipalities needing to build up resilience to flood or drought – and to rebuild when investments in resilience fall short.

Q&A

Praveen Gupta: The US is surely and steadily moving in the direction of ‘uninsurability’. Homes and auto are the first stop. When could it reach the Oil and Gas segment?

Michele Wucker: The past year’s mounting losses in places vulnerable to hurricanes and wildfires made it clear to insurers that property coverage in those areas was no longer a good risk-reward proposition.

Insurers face bigger underwriting and investment choices in oil and gas. Do they want to keep insuring fossil fuel activities that are costing them more and more in extreme weather-related claims and lost business where it has become impossible to keep insuring clients? Activist shareholders and plaintiffs in lawsuits by more than 20 US cities, states, and non-profits are trying to convince them that the answer is no.

Some insurers have taken steps to cut back on their underwriting of oil and gas. It’s still nothing near as many companies nor as bold as what climate activists want to see. And it lags activists’ success in pushing insurance companies to exit coal. But there is increasing momentum.

Oil and gas insurers will see more and more shareholder proxy voting campaigns asking insurers to report how specifically they plan to support greenhouse gas reductions. Several recent activist campaigns appear to be having a small amount of impact even though they got minority support in the 30 percent range and were non-binding anyway.

A growing number of states and cities – including Chicago, where I live – are suing fossil fuel companies because of their climate impact. If courts start ruling for the plaintiffs, that could make a difference in insurability.

PG: As this unfolds in the US, developing countries are trying to increase their insurance penetration?

MW: Insurance regulators and companies in the US market are looking closely at protection gaps related to extreme weather. Most likely we will see gaps increasing in some areas as insurers withdraw or raise prices so high that property owners opt to “self-insure.” But gaps may narrow elsewhere as property owners become more concerned with protecting themselves.

“Increasing insurance penetration in developing countries likely will require a blended finance approach”

The dynamic in developing countries is so different from developed countries that it’s practically an apples-versus-oranges scenario. First, the protection gaps are much wider and penetration rates are much lower. Many of the most climate vulnerable areas are also the least likely to be insured and the least likely to be able to afford insurance.

Increasing insurance penetration in developing countries likely will require a blended finance approach; this scenario could combine development bank financing for resilience and adaptation with some carefully targeted private sector policies in areas with more awareness of and ability to afford insurance. Increasing interest in catastrophe bonds and global risk pooling may play a part as well. And, more controversially, climate resilience also may require moving people from climate-vulnerable areas to higher ground or less water-stressed areas.

PG: What numbs humans to recklessly ignore climate risk?

MW: Humans’ reckless ignorance of climate risk is the consequence of a combination of influences. First is what some social scientists call “solution aversion” which is a tendency to deny the seriousness of problems when we don’t like the solution. This is quite prevalent in part because most humans don’t like change of any kind, so solution aversion comes into play more than we think.

Manufactured denial also comes into play: people who don’t like solutions to climate change because they are making money from dirty energy know that they can exploit human nature.

“I think it’s important to call out as false – that climate change is “slow moving” and something that will happen in the future”

The media also comes into play. Here I hesitate to repeat the mistaken impression they disseminate, lest I reinforce it, but I think it’s important to call out as false – that climate change is “slow moving” and something that will happen in the future.

It’s here now: extreme weather, rising seas and inland water levels, droughts, wildfires. Finally, a sense of agency is important, but climate change feels so big that many people feel powerless, even though we have more power than we think.

PG: Insurers understand risk. Yet they – the large American ones in particular – continue to invest in and insure the very reasons responsible for the Climate breakdown?

MW: It’s very much in insurers’ interest to help solve the climate crisis, and you’re right – it’s a big problem that many insurers continue to invest in and insure the fossil fuel industry. If you insure coastal real estate, businesses and individuals who are prone to flood or fire damage, or any other entities vulnerable to climate change-induced extreme weather, why would you want to contribute to the very influences that put your insured clients – and in turn, yourself – in harm’s way? That question is especially apt when it’s clear that fossil fuels are at a turning point when both investors and policy makers are going to be making big changes.

There has been rising concern by financial regulators and by insurers themselves over whether the industry has enough capitalization to withstand expected losses caused by climate change, and it’s time to stop hand-wringing and take serious action. The insurance industry also is well positioned to push for meaningful changes by insured entities. Just like many auto insurers reduce your premiums for avoiding accidents, driving fewer miles, and allowing apps to monitor (and hopefully improve) your driving habits, there are so many ways that insurers could nudge clients to reduce their carbon impact.

PG: Many thanks, Michele for the eye-opening insights from time to time. How I wish the insurance industry wakes up to your warnings.