The Journal, Chartered Insurance Institute

November 28, 2023

When I was invited to write this piece for the Insurance Brokers Association of India (IBAI) – some months ago – the net-zero insurance alliance (#NZIA) implosion was a dominant thought. Global insurers abdicated an opportunity to own and address climate breakdown. Now this scorecard!

Is there another possibility? Could some international insurance broker/s take on the transformative role?

In a scenario where the fossil fuel industry was to strand – it could not only impair risk carriers but all those in the supply chain including intermediaries facilitating such a portfolio.

Apart from fossil fuel becoming history, Climate breakdown would deal a body blow to the current format of insurance both in terms of affordability and availability. Could Parametric be the new avatar? Any nimble player/s who may leverage such scale and complexity of disruption?

Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership’s (CISL) new briefing – Risk sharing for Loss and Damage: Scaling up protection for the Global South offers a breakthrough in the design of the global architecture for Loss and Damage (L&D).

L&D in the international policy debate broadly refers to efforts to “avert, minimise and address loss and damage associated with climate change impacts, especially in developing countries that are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change”. This blog provides a backgrounder.

It would use the economic efficiency of risk capital markets, which can convert modest annual flows from donors into major contractual entitlements for vulnerable countries when disasters strike, now and through to 2050.

Members of Howden Climate Parametrics modelled the technical cost and financial protection that could be achieved by using some L&D funds to access international risk capital markets. The action plan proposes to protect all 30 small climate vulnerable countries (population less than one million), from losing more than 10% of their GDP from climate shocks. It also advocated providing each L&D eligible country with $10m of annual premium to protect their highest priority needs.

The L&D domain includes Small Island Developing States (#SIDS), Least Developed Countries (#LDCs) and Vulnerable Twenty (#V20).

All this is happening outside the ambit of traditional insurance. The format does not entail a transactional relationship – always taken for granted. A broker facilitating an out of the box solution. Howden just took a significant first step. Is this a writing on the wall?

November 22, 2023

Illuminem.com

‘What happens when you put a fossil fuel exec in charge of solving climate change’ – screams a headline. The challenge is not about climate deniers alone. It is also an ever-evolving jargon and a seemingly never-ending analysis paralysis. Then there is a lot that believes something ought to be done but procrastinate. Caught in this bind, how do we move ahead? What will it take to break out of this inertia?

Twice this week we’ve seen the planet’s temperature briefly surpass 2 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels for the first time in recorded history.

Over the last two years, as a backgrounder to the #COP, I have had the pleasure of hearing from outstanding upcoming women leaders. Focus being diversity and inclusion, given the serious gender bias. This time I had the privilege of speaking to renowned international leader Dr. Gillian Marcelle, PhD. She is super excited and keen to address the biggest existential crisis we have ever faced.

Gillian has vast experience in the design and implementation of blended finance strategies that often involve partnerships, #ecosystem strengthening and #designing architectures for #transformational change. At the helm of Resilience Capital Ventures (RCV) it is her endeavour to support efforts to restructure #internationalfinancialsystems in ways that benefit the #developingworld.

“Therefore, the relevance of COP28 UAE, in my view, is that these conferences continue to move the world forward by providing an albeit imperfect process of figuring out how to solve problems that extend beyond national boundaries”, says Gillian.

“This media and Western NGOs display a very different posture from the UK, where the Glasgow hosted COP26 was presented as the venue where the private sector would swoop in and take over climate finance. We all know how that turned out”, she cautions.

Gillian’s bold prescription: “Narrative change in finance and economics to place responding to the #polycrisis at the center of economic and investment strategies; movement building to tap into the knowledge of #climate and #social #justice advocates and activists around the world; and activating all forms of capital at scale with ecosystem strengthening efforts done in parallel”.

#Bridgetowninitiative

Mia Amor Mottley

Dr. Gillian Marcelle leads Resilience Capital Ventures LLC, (RCV), a boutique capital advisory practice specializing in blended finance. She has a proven track record in attracting investment and focuses on telecoms, fintech, renewable energy and regenerative agriculture. Her clients and partners include: The government of The Bahamas, MPC Energy Solutions, PolicyLink, Marin Agricultural Land Trust (MALT), AfricaBio and the Clinton Foundation. She currently serves on the Advisory Board of New Majority Capital and has guided numerous ventures in the role of Senior Advisor. Her specialty is the design and implementation of blended finance strategies that often involve partnerships, ecosystem strengthening and designing architectures for transformational change.

Gillian’s educational background includes earning degrees in Economics from the University of the West Indies, St Augustine, Trinidad & Tobago, and the Kiel Institute of World Economics, Germany; an MBA with a specialization in high technology management from the George Washington University and a doctorate in innovation policy from the Science and Technology Policy Research Unit, SPRU, University of Sussex. Her international public service includes appointments with the Global Building Network; several agencies in the United Nations system; World Economic Forum, Global Future Council on SynBio; and an appointment as a Commissioner on the Value Commission, a project of the Capitals Coalition.

PG: It is time for yet another COP. Do you see its ongoing relevance despite an oil-rich nation playing the host?

GM: The fact that the host of COP28 is the United Arab Emirates, a Gulf state country, has generated a lot of attention in the US and Europe and even calls for a boycott.

My country of origin is Trinidad and Tobago, an energy-led economy, and so simply from the point of view of hypocrisy, it would be silly for me to take a negative attitude towards the UAE.

Then there is this – the UAE is pursuing ambitious decarbonization and energy transition strategies as outlined in its National Determined Contribution (NDC) and the UAE Energy Strategy 2050.

UAE more than triple the share of renewable energy by 2030 to stay on track with its climate change mitigation goals, as well as help increase the share of installed clean energy capacity in the total energy mix to 30 percent by 2030.

The plans include:

…a broad range of measures including renewable and nuclear power, reverse osmosis desalination, improved efficiency, district cooling and demand-side management, carbon capture and storage (CCS), hydrogen use in industry, fugitive methane cutting, public transport and electric vehicles, innovative agricultural technologies, and others.

Source: Commitments and Contradictions: Gulf and Middle East Decarbonization Strategies Ahead of COP28. These efforts to make accelerated progress to reach net zero emissions by 2050 will be achieved by commitment of size-able investment with reported investments reaching USD 53 billion.

UAE has also strengthened its institutional apparatus in the following ways:

The UAE was the first Gulf state to announce a national climate strategy in 2017 and was also the first to link its climate strategy with its economic development plans, for which the UAE Green Agenda 2015-2030 was established as an overarching implementation framework. The UAE Council on Climate Change and Environment, established in 2016, is the committee responsible for overseeing the implementation of the Green Agenda. Source: The GCC and the road to net zero.

Moreover, the UAE has orientated itself in support of the concerns and negotiating demands of the developing world.

The relevance of COP28 UAE, in my view, is that these conferences continue to move the world forward by providing an albeit imperfect process of figuring out how to solve problems that extend beyond national boundaries.

The UAE supports green infrastructure and clean energy projects worldwide and has invested in renewable energy ventures worth around 16.8 billion USD in 70 countries with a focus on developing nations. It has also provided more than 400 million USD in aid and soft loans for clean energy projects. Source: The UAE’s response to climate change.

As part of its leadership role, the UAE through the COP Presidency has been active in offering support for the L&D Fund and led the way for standing up coalitions for accelerating renewable energy. Working with sixty countries including US, EU, South Africa and Vietnam among them, to make a high ambition pledge to scale down coal and triple investments in clean and renewable energy by 2030.

Notwithstanding all of these measures, commitments and policy advance, the UAE and other Gulf States face heavy criticism for maintaining and even expanding oil and gas production. It will be important going forward to monitor and hold accountable all fossil fuel providers with robust tax regimes, local supplier development initiatives and initiatives to invest oil and gas windfall profits in energy efficiency and accelerated rollout of renewable energy.

This media and Western NGOs display a very different posture from the UK, where the Glasgow hosted COP26 was presented as the venue where the private sector would swoop in and take over climate finance. We all know how that turned out.

As far as the relevance of the UNFCCC Conference of Parties negotiations go, many commentators, particularly those from the Global South, know that there is value to multilateral venues where the voices and votes of small and less powerful countries count.

Therefore, the relevance of COP28 UAE, in my view, is that these conferences continue to move the world forward by providing an albeit imperfect process of figuring out how to solve problems that extend beyond national boundaries.

I echo the views of Amb. Selwin Hart and the UN Secretary General in calling upon member states and non-state actors to use these opportunities well, to display more ambition and increase the proportion of adaptation finance.

For those very strongly concerned about the host of this year’s COP, they can wait until COP29 in Brazil to engage.

PG: Any thoughts on developed countries trying to push the L&D Fund out of the UNFCC? How and when does it become fully functional?

GM: My support for the L&D Fund is a matter of record. I saw the recent pieces regarding the recommendations of moving the secretariat out of the UNFCC.

Those of us concerned about establishing a mechanism to mobilize and deploy funds that compensate countries for cumulative and historical loss and damages arising from climate change regard any kerfuffle about bureaucratic arrangements as unnecessary delays.

When countries in the Global North wish to mount collaborative or national responses to natural disasters, wars, or pandemics, they find ways to proceed. Therefore, the agreement reached in early November were very welcome and set the stage for the Loss and Damages Fund to be on the official agenda.

Western media has, by and large, failed to cover this issue with balance and nuance. The road bumps are celebrated and presented as news without the corresponding long form investigative pieces to build commitment.

There are models of effective execution of large-scale financing that can be used as examples. It is also likely that the origin of the L&D Fund will have to be recognized if it is to have legitimacy. The scale of the financing required is certainly daunting.

As Avinash Persaud, advisor to Prime Minister Mia Mottley of Barbados, said when quoted in a recent Financial Times piece, progress on the L&D Fund should be regarded as a shared and important objective of the entire international community.

Western media has, by and large, failed to cover this issue with balance and nuance. The road bumps are celebrated and presented as news without the corresponding long form investigative pieces to build commitment.

There are very few journalists providing a sense of progress. As I have said before, “facts will not stop those who cannot drag their hearts and minds away from nomenclature wars and/or endless debates as to whether carbon taxes and voluntary initiatives work.”

The roll-your-sleeves-up-and-get-it-done community that is designing, deploying and evaluating solutions for the polycrisis should be amplified more. We are going to be using COP28 UAE as a focusing device for our efforts; A meeting place and venue for dialogue and knowledge sharing outside of the formal negotiations.

PG: The burgeoning Climate Crisis is defying all timelines and deserves urgent action. Aren’t there too many distractions getting in the way?

GM: I do not foresee any time soon where there will be no noise and distractions. In my view, what is required is: narrative change in finance and economics to place responding to the polycrisis at the center of economic and investment strategies; movement building to tap into the knowledge of climate and social justice advocates and activists around the world; and activating all forms of capital at scale with ecosystem strengthening efforts done in parallel.

What is required is: narrative change in finance and economics to place responding to the polycrisis at the center of economic and investment strategies…

I am encouraged to see efforts along these lines in countries as diverse as Uruguay, where 98% of all energy is derived from renewable sources, and the United States, with billions in annual federal spending on climate under the Biden-Harris Administration.

Figure 1: U.S. Annual Federal Spending on Climate (1990-2027)

Source: RMI

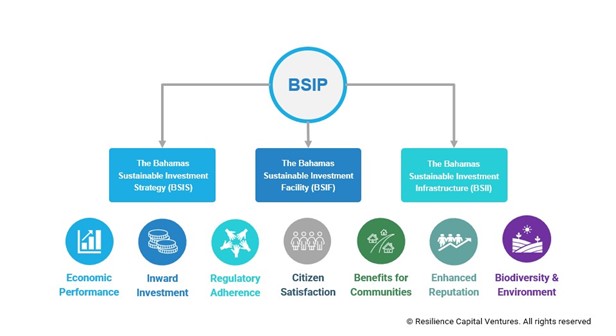

PG: Would you please share what ‘The Bahamas Sustainable Investment Program (BSIP)’ is about?

GM: The Bahamas Sustainable Investment Program (BSIP) is an ambitious multi-year investment and economic development program. BSIP seeks to position The Bahamas at the forefront of sustainable investment trends and deliver socio-economic benefits to the people of the country in line with national development goals and existing commitments on climate change and environmental response. This initiative is important for delivering on the government’s vision of a transformed economy and society.

Figure 2: The BSIP Overview

Source:The Bahamas Sustainable Investment Program

Once implemented, the BSIP will mobilize high-quality investments that produce risk-adjusted returns and positive social impact while adhering to global ESG standards and sustainability philosophies. This initiative will position The Bahamas as an even more attractive investment destination to global investors and align the domestic investment policy framework with global trends. Powered by the BSIP, The Bahamas will become a demonstration site showcasing what is possible when astute government leadership directs institutional development and facilitates private sector investment.

PG: What would be the role of Resilience Capital Ventures and how do you propose to address sluggishness in capital growth and reduction of misallocation decisions?

GM: The BSIP is designed by Resilience Capital Ventures (RCV) and we lead its execution on behalf of our client – the government of The Bahamas. This program serves to accelerate investment in mitigation, adaptation, and disaster management. By bringing together professionals skilled in capital markets, risk management, issuing securities, underwriting and placement, the program focuses attention of global capital markets on an underserved market. This is critical for success. Our focus draws on the dynamism of private sector firms in light of the many challenges that Development Finance institutions, quasi-public funds, and Multilateral Development Banks have with sluggishness and long lead times for deployment. Even the new President of the World Bank Group has taken aim at unnecessary bureaucratic processes as part of his plan for improvement.

Misallocation decisions arise out of gaps between actual and perceived risks and low levels of contextual knowledge and experience.

In my view, misallocation decisions arise out of gaps between actual and perceived risks and low levels of contextual knowledge and experience. Financiers take the easier and more familiar investment opportunities first. This means they rarely get to small islands in the Caribbean. This is not because of the inherent value, attractiveness, or necessity but simply because these jurisdictions are not top of mind.

Our approach draws on my pioneering experience in taking African telecom companies to global capital markets and more recent experience in helping private equity clients raise capital for renewable energy projects. My own experience is complemented and enhanced by a senior team with decades of experience and a track record of accomplishment. RCV is fortunate to have retained an entire bench of finance and development professionals, including members of the Diaspora, who are frankly fed up with the mediocrity that gets presented to governments in our countries of origin. We know that this is not the best in class and now have an opportunity to demonstrate what is possible and are putting accountability for our outputs up for scrutiny.

PG: Is there a synergy with the Bridgetown Initiative?

GM: It is possible for small island nations in the Caribbean to innovate in multiple directions at the same time. Our work on The BSIP is focused on the design and execution of capital market solutions and therefore, in alignment with and additional to the recommendations of the Bridgetown Initiative.

The articulate advocacy of Prime Ministers Philip Davis of The Bahamas and Mia Mottley of Barbados has raised the profile of the Caribbean at a time when this is sorely needed. However, it is important that no initiatives are pitted against each other because of intellectual laziness or lack of familiarity.

We at Resilience Capital Ventures are supportive of all efforts to restructure international financial systems in ways that benefit the developing world. We also join others in commending the leadership of Barbados in spearheading those efforts.

Praveen, thank you for the opportunity to share these views as the international community gets ready for COP28 in Dubai. With the conflict and war in the world, it is very important to focus on ways that we can move forward towards desired future states where humans and other species thrive and we do a better job of stewarding planet Earth.

PG: It is a real pleasure, Gillian. Many thanks for your unique insights and perspective. My best wishes in all your endeavours.

Alison Taylor is a clinical associate professor at NYU Stern School of Business, and the executive director at Ethical Systems. Her previous work experience includes being a Managing Director at non-profit business network BSR and a Senior Managing Director at Control Risks. She holds advisory roles at VentureESG, sustainability non-profit BSR, Pictet Group, and Zai Lab, and is a member of the World Economic Forum Global Future Council on Good Governance.

She has expertise in strategy, sustainability, political and social risk, culture and behavior, human rights, ethics and compliance, stakeholder engagement, anti-corruption and professional responsibility. Her book Higher Ground: How Business Can do the Right Thing in a Turbulent World will be published by Harvard Business Review Press in February 2024.

Alison received her Bachelor of Arts in Modern History from Balliol College, Oxford University, her MA in International Relations from the University of Chicago, and MA in Organizational Psychology from Columbia University.

Praveen Gupta: “Corporate America is finding itself trapped between society’s progressive impulses, and the conservative backlash”?

Alison Taylor: This is certainly true. But I think it’s been a long time since the world saw America as a role model. Lots of people still want to live here, for the economic opportunity and dynamism. But whether it is guns or reproductive rights, America has plenty of issues that make it a poor role model.

PG: What do you see in the crystal ball?

AT: Gosh I have no idea. The next election is terrifying. Clearly we are past the era of globalization and in a much more fragmented, contentious, fraught period where commitments to democracy seem increasingly fragile

PG: Why is delivering on both profit and purpose getting increasingly complex?

AT: I think it’s always been complex. One challenge is that no one agrees on what “purpose” actually is. Another is that doing the right thing, or even just focusing on environmental and social issues, is sometimes profitable, sometimes not. Timeframes, and investing for the long term in an unpredictable world, further complicate things. A final problem is that corporate value itself has become more intangible and perception based. It has reached the stage where we can’t even agree on terminology, let alone discuss the actual problems.

Recruiters want more international backgrounds, more career variety, more sustainability knowledge, better social skills, humility, and understanding of influence, not just barking orders from the top.

PG: A quieter leadership cohort in favor of collaboration and humility remains a minority vis-à-vis Silicon Valley god/emperor model?

AT: One point a smart reader of my upcoming book (see here for more details: https://www.amazon.com/Higher-Ground-Business-Right-Turbulent-ebook/dp/B0BTMRCCC1) made is that often this new generation of quieter leaders are just fronts for the existing founders and shareholders, who are now all neatly moving themselves into “executive chair” roles. But, notwithstanding that, there is recruitment data showing that what we are looking for in senior leaders is changing. Recruiters want more international backgrounds, more career variety, more sustainability knowledge, better social skills, humility, and understanding of influence, not just barking orders from the top.

PG: Milton Friedman’s compelling case for maximizing profit still prevails. Shouldn’t business schools be addressing this?

AT: I am not sure I agree. Businesses must make a profit to survive. Very few of the younger students I teach think that business exists solely to make a profit. To borrow a line from my book, humans need hearts to survive, but don’t exist solely to act as vehicles for their beating hearts. There is an expectation that business should treat workers properly and clean up its own mess. And interestingly, that position is not particularly partisan.

Many of the most powerful faculty continue to approach these questions in a way that might be argued is anachronistic.

On business schools, many of the most powerful faculty continue to approach these questions in a way that might be argued is anachronistic. I think the important thing is to not insist that professors parrot a certain worldview, but to open up the space for scrutiny and debate. We can disagree and debate ideas, that’s what a university is for.

PG: Wasn’t it Friedman who unleashed forces of corporate greed leading us down the path of Climate Breakdown?

AT: The problem is not so much Friedman but how he has been interpreted. Perhaps he was right IF there is a clean and clear line between business and politics. There isn’t.

PG: Does it make sense to continue treating branding, culture, sustainability, risk, and ethics as separate disciplines?

AT: My book is about why it does not.

PG: Moreover, performance matrices have little room for ethics?

AT: Some performance matrices consider not just whether a target was achieved, but how it was achieved. High performing assholes are the big vulnerability in a lot of organizations, not least because this encourages kick down/kiss up behavior.

In my book I recommend grounding a corporation’s ethical commitments in its impact on human beings.

PG: A deep global hunger for inspirational leadership prevails. Why are business schools unable to address the scarcity in moral leadership?

AT: I don’t know if business schools exist to teach moral leadership, and at least at Stern, there is quite a bit of focus on helping students to be better, more effective and ethical leaders.

One issue that is frequently raised is that personal and organizational ethics are not the same thing, and we are in a highly contentious and polarized era. In my book I recommend grounding a corporation’s ethical commitments in its impact on human beings.

Exercise practical curiosity about this, treat people with dignity and respect, make your best possible effort to do no harm and clean up your own mess. Interestingly, none of this is partisan and all of it is in line with how society would like business to behave!

PG: It’s been a real privilege tracking the evolution of your book and I am amazed how you draw in all the rapid-fire unravelling. Truly compelling. My best wishes for the upcoming launch, Alison!

In conversation with the brilliant Andrea Edwards

November 2, 2023

October 30, 2023

Illuminem.com

https://illuminem.com/illuminemvoices/not-all-tech-is-insurtech

My Op-Ed for illuminem, originally published by the Chartered Insurance Institute Journal.

Allow me to start with this post by eminent ethics professor and author Guido Palazzo: https://lnkd.in/dxcbEJPw.

“A Swiss startup that developed a software solution that helps to increase honesty in business transactions accuses Zurich Insurance to have stolen their idea and obviously they can provide the evidence”.

If this story had broken a couple of weeks ahead – it would have given a twist to my tale. Even though this does not have a US origin. My focus being some assorted tech related stories from several covered by American media – during past 3 months – demonstrate how technology interfaces with diverse aspects of daily life. And insurance in turn intersects with them.

The implications go far beyond world of insurance. While InsurTech draws much attention, there is so much else that also merits it if we must expeditiously address the bigger world of #ESG.

Needless to mention that all forms of interface demand heightened #stewardship from insurers. Be that as carriers, risk managers or investors.

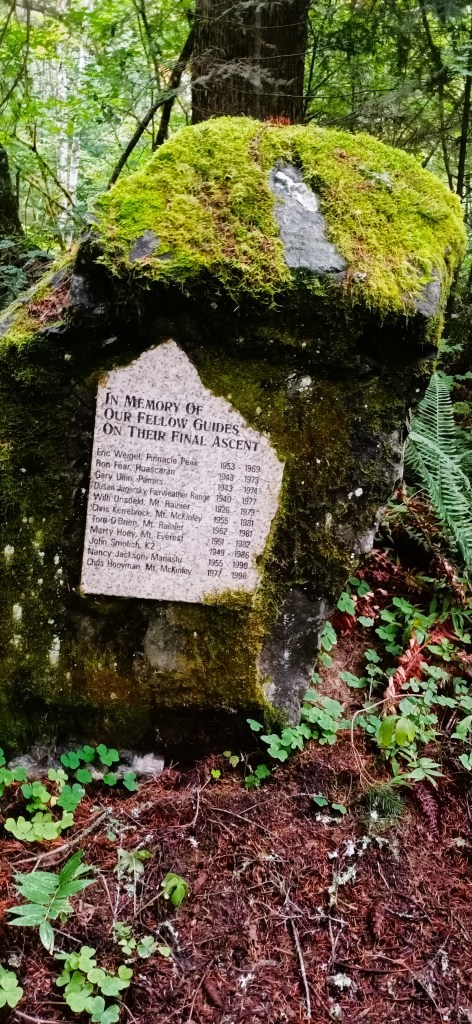

Who but Lahkpa Sherpa knows it best.

Speeding past Ashford – located on the north side of the Nisqually River and the main access road to Paradise in Mount Rainier National Park – you just might miss out on the low profile ‘Wild Berry Restaurant’. Wishing for a “Taste of Two Worlds”? This is where you ought to stop by. It serves both traditional American Mountain Menu as well as authentic Sherpa-Himalayan food from Nepal.

What’s really special about this place is the owner – an iconic mountaineer who has made it his abode. Mount Rainier, a glacieated and active volcano in Washington state, may be just half way the Everest, but the region has been a nurturing ground for mountaineers aspiring to scale them all.

What better proof than this testimony inside the forest at Ashford?

A view from ‘Paradise’ (base camp): Mount Rainier, 14408 feet in altitude, is the highest peak in the Cascade Range. It is the heart of Mount Rainier National Park.

Splash of colours just ahead of the weather conditions become challenging.

The legend

Five sisters of Orting, as the Puyallup legend goes – were transformed into five mountains by Doquebuth, the changer. One of them was called Takkobad – that is Mount Rainier. Doquebuth said to Takkobad, “You will take care of the Sound country. You will supply water. You will be useful in that way.”

Mount Rainier is one of the snowiest places in the United States. Thanks to 645 inches of annual snow that it receives, Takkobad generally fulfills Doquebuth’s wish.

Wild Berry opens from May to mid-October and does not operate on Tuesdays!

The legendary Sherpa

Born in Nepal, Lhakpa Gelu is best known for holding a world record for the fastest ascent of Mount Everest in 10 hours 56 minutes and 46 seconds. Gelu’s record breaking trip was his tenth to the Everest summit. He has scaled it fifteen times (both North Ridge and South East Ridge).

Like an invisible character, he moves between the kitchen and the tables keeping a watchful eye in a supporting role. He demands no attention and perhaps much of the time most customers are not even aware of his presence amidst them. Just as he ascends the summits without fanfare, and descends. Sees it no longer but has seen it all. Before soon gets to see them yet again.

Other than the Everest, he has also been atop Mt. Denali, Mt. Ama Dablam, Mt. Cho Oyu, Mt. Baruntse, Mt. Aconcagua and Mt. Rainier. For sure, the most accomplished Sherpa mountaineer.

Yes, you cannot stay on the summit forever. But you could re-visit and pursue new ones, Lhakpa Gelu way, too. From the road to picturesque Paradise.

The Journal, Chartered Insurance Institute

October 23, 2023

https://thejournal.cii.co.uk/2023/10/23/current-climate

Not all tech that insurers interface with is #Insurtech. However, growing ESG demands and the resulting responsibilities demand heightened stewardship from insurers. Be that as insurers, risk managers or investors.