REPORTS AND ANALYSIS | | Nov 8, 2022

Former international insurance CEO, Praveen Gupta, a thought leader on financial governance and risk, looks at the RBI’s climate change consultation process in the context the global finance sector’s and regulators’ approaches to climate risk, drawing on examples from various world economies.

http://www.thediversityblog.com

Young-Jin Choi leads the impact and ESG practice at Vidia Equity, a newly established purpose-driven Private Equity climate impact investor. Prior to joining Vidia, Young-Jin served as the impact investing advisory team’s Head of Research at PHINEO gAG, a leading think-and-do-tank in the German speaking area with a focus on impact measurement and management.

Young-Jin’s previous roles include investment management at 3M’s corporate venture capital unit and strategy consulting in a variety of industries and regions with Monitor Group (now Monitor Deloitte). He holds three master’s degrees in Mechanical Engineering (RWTH Aachen), International Business Studies (University of Maastricht) and Politics, Philosophy and Economics (LMU Munich).

Here are Young-Jin’s diagnoses and the prescriptions, on the eve of #COP27, as he responds to these questions in context of my submission to the Reserve Bank of India on Climate Change consultation.

Praveen Gupta: Would you agree that a fragmented financial regulatory governance makes it more fragile whilst dealing with a climate emergency? Do you think the time to talk about Climate Crisis is running out and it is Poly Crisis that we ought to be addressing?

Young-Jin Choi: The fundamental nature of the problem includes the way our current economic and financial systems are currently designed to work (in terms of purpose, goals, rules, incentives, et al), resulting in a severe market failure. Dealing with the climate emergency requires addressing this market failure, which in turn requires a concerted, coordinated approach between various regulatory institutions, within a country as well as internationally. Financial system regulation can be most effective, when complementary economic system regulation is in place, but it can also be rendered ineffective when the economic system design continues to distort risk – and return profiles in connection with greenhouse gas emissions.

Various humanitarian, economic, geopolitical and stability-related crises continue to be induced and exacerbated through rising global temperatures and extreme weather events.

While it has become more important now to address multiple crises at once (through “multisolving”), I believe it is similarly important to maintain a sharp focus on the climate crisis as the singular, overarching long-term driver and multiplier of various risks and crises. Various humanitarian, economic, geopolitical and stability-related crises continue to be induced and exacerbated through rising global temperatures and extreme weather events, as the analysis by Chatham house of “cascading systemic risks” illustrate: https://www.chathamhouse.org/2021/09/climate-change-risk-assessment-2021/04-cascading-systemic-risks.

PG: What would your advice be to money pipelines in terms of impact investing and decarbonisation?

YJC: I would advise capital allocators to take a broader, science-based social systems perspective, taking the sustainability context and ethical minimum aspirations and thresholds into account, when assessing the desirability – as well as undesirability – of an asset’s impacts. Beyond the impact of the asset’s operations and supply chains, this also includes the direct and indirect impacts generated by an asset’s sale of products and services. It should be clear, for instance, that financing further fossil fuel-based greenhouse gas emissions (especially from new fields and projects) is simply inexcusable in a time of grave climate emergency – regardless of their (unethical) profitability and their own operational decarbonization efforts. The same applies to products and services that support or enable fossil fuel operations. At the same time, products and services that significantly support or enable climate solutions deserve proper recognition, too, besides the climate solutions themselves. Of course, climate solutions are not exempt from serious ESG issues and risks – those need to be carefully managed and mitigated over time but shouldn’t represent a dealbreaker per se.

When thinking about putting a price on carbon emissions, it is important to redistribute most of the income generated this way to affected households in order to ensure their continued political support and help lower income households transition. When thinking about rewarding carbon removal, it is important to transform current voluntary carbon markets into a global pay-for-success scheme.

Even if we should and wanted to act as if we all were universal owners and as if ethical materiality matters at least as much as financial materiality, our current instititutional frameworks, mandates, and duties don’t provide institutional investors with the same freedom that an autonomous moral agent enjoys. Moreover, it should be clear that simply cleaning up a single portfolio from polluting fossil fuel assets won’t be enough as long as the asset continues to operate under different ownership. It would also be naïve to expect a fossil fuel company to voluntarily retire a business that is allowed to remain highly profitable. Maintaining ownership of a fossil fuel asset creates an unavoidable economic conflict of interest when it comes to advocating for strong climate policies that would force an accelerated phaseout of fossil fuel production/demand and asset stranding.

We need to recognise these practical legal and economic constraints when it comes to the impact potential of portfolio company engagement and voluntary pledges. We need systemic interventions to improve the alignment between the scale and pace of capital allocations that are normatively needed and the empirical universe of available investable assets that is determined by mandates and duties as well as the way the market prices (or fails to price) impacts.

PG: Do you prescribe carbon pricing as a tool and would it work as one-size-fits-all?

YJC: Carbon pricing – which should include the whole carbon pricing matrix as described by Delton Chen (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6LAiYb4k0go) represents a key instrument needed to accelerate decarbonisation. When thinking about putting a price on carbon emissions, it is important to redistribute most of the income generated this way to affected households in order to ensure their continued political support and help lower income households transition. When thinking about rewarding carbon removal, it is important to transform current voluntary carbon markets into a global pay-for-success scheme, as suggested by the https://globalcarbonreward.org/.

Other key instruments include strong climate policies (e.g. mandatory minimum standards and replacement mandates) as well as increased green fiscal spending e.g. for enabling infrastructure (flexible, integrated power grids) and or de-risking and subsidising climate finance. These instruments need to be combined in a coherent policy package. Its transformational acceleration affect partly depends on their relative strength – higher carbon pricing and/or bolder climate policies can allow for less fiscal spending, and vice versa.

Companies respond with hyperbole instead of admitting that they cannot do what is needed by themselves. But they have a corporate political responsibility.

PG: How big a menace is greenwashing? Do you see effective action coming from regulators?

YJC: There is no doubt that greenwashing is a serious problem that drives complacency and waters down our collective sense of climate urgency. But stricter disclosure and transparency standards won’t by themselves fix market failure. A trend reversal into “green hushing” is not helpful either. In connection with greenwashing, I see an even bigger meta-risk in not recognising greenwashing as what it often is – a sign that voluntarism and current frameworks are insufficient to promote genuine transformations. Companies respond with hyperbole instead of admitting that they cannot do what is needed by themselves. But they have a corporate political responsibility: https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=54635.

If they were honest about their economic and legal constraints and limitations, I’m sure that they would more strongly advocate for governments to set binding rules, mandatory standards, increase fiscal spending for subsidies and de-risking, price carbon etc. They would make industry associations and thinktanks to support their views or cease support, rather than allowing market failure to continue.

“Unfortunately, the history of COPs doesn’t fill me with much hope. Neither does the counterproductive rise of ultranationalism into positions of government authority in various countries”.

PG: Any thoughts on the relevance of ‘The Ministry For The Future’ in today’s global context?

YJC: I think Kim Stanley Robinson’s book does a great job at showing a possible future in which we barely manage to turn the ship that is our civilisation around. Among the interesting solutions he explores, there is one which I believe represents a critical success factor: Inspired by Delton Chen’s Global Carbon Reward initiative (www.globalcarbonreward.org), the author describes how central banks eventually start to collaborate and mobilise enormous additional financial resources via a carbon currency that are then used to reward successful climate mitigation efforts (and even compensate Petrostates for leaving their fossil resources in the ground). This way, we can transform voluntary carbon markets into a global pay-for-success scheme, in which corporates are incentivised to participate rather than having to purchase carbon credits, and make sure that the carbon price (exchange rate) is as high as needed to serve its purpose.

Most importantly, the post-colonial hypocrisy needs to end …

PG: Do you see COP27 as a catalyst for a fundamental shift?

YJC: Unfortunately, the history of COPs doesn’t fill me with much hope. Neither does the counterproductive rise of ultranationalism into positions of government authority in various countries. It will be more pragmatic if committed large emitters form a climate club (https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-00736-2) and use carbon border adjustment mechanisms, technology transfers, and additional development cooperation resources in order to globally promote and incentivise decarbonisation.

Most importantly, the post-colonial hypocrisy needs to end – developed nations cannot insist on developing their own fossil resources, and fail to deliver the international financial support they had promised. Developing nations are expected to fund the clean energy transition by themselves while voluntarily forfeiting fossil fuel export income. Every country on Earth has the ethical obligation to sign the fossil-fuel non-proliferation treaty and ensure that we keep fossil fuel reserves in the ground.

PG: Many thanks Young-Jin for these exceptional insights backed by scholarly findings. Here is wishing you all the very best in your endeavours!

My column in the illuminem: October 26, 2022.

https://illuminem.com/illuminemvoices/b2d325f5-37bc-4c89-81d3-ba41e2fb2f0c

Every other day we hear of a new manifestation of greenwashing. While on the one hand companies and countries have vied for green pledges leading to an illusory #netzero , they resort to the likes of sportswashing or nature rinsing to delude the world. That has become a sport by itself!

“We’re… seeing a growing trend for greenwishing where companies set hugely ambitious climate targets, with little or no clear plan to achieve them. That might help companies in the short term, but without realistic targets they’ll be on a hiding to nothing.” Matthew Bell observes in EY’s annual Climate Risk Barometer (many thanks Zsolt Lengyel).

“#Greenwashing is a marketing or advertising strategy where corporations recognise environmental problems but then use misleading or false information to make it appear as if they and the products they sell are providing solutions to these problems”, explains Hans Stegeman.

New research demonstrates that industry associations representing key sectors and some of the largest companies in the world are lobbying to delay, dilute and rollback critically needed policy aimed at preventing and reversing biodiversity loss in the EU and US. Highlights InfluenceMap.

Biodiversity loss due to human activity is occurring globally at unprecedented rates and faster than at any other time in human history. Despite increasing awareness of the #biodiversitycrisis, the world failed to meet any of the UN biodiversity targets for the last decade, reminds Influencemap.org. And, at the UN Biodiversity Conference (#COP15) due to be held in Montreal in December, governments from around the world will negotiate the post-2020 global biodiversity framework; a set of targets and goals for the next 10 years aimed at reversing biodiversity loss.

“The rise in litigation is important but it is the rise in regulation internationally, the growing robustness of regulators and the sharing of information and strategy amongst regulators that is more impressive. The SEC, BaFIN, ASA, CMA, FRA, EA, SEPA, EPS. FRC, DoJ, the Police in UK and Germany, Dutch Advertising agency, etc. which may be as important as litigation”. Professor Paul Watchman gives us some hope.

In the meantime, the US public relations firm Hill+Knowlton helping Egypt organise #COP27 also works for major oil companies and has been accused of greenwashing on their behalf, according to openDemocracy. Hill+Knowlton’s clients have also included Coca-Cola.

Is the world’s biggest annual climate event headed for a fizz?

http://www.thediversityblog.com

Cindy believes the most effective change we can make is in how we shape the mind-set of the rising generation and how we design our organisational systems. Her children’s book Bright New World is published by Welbeck in October 2022. She sits on various advisory boards and the steering committee of ‘She Changes Climate’, campaigning for full inclusion of women’s voices on planetary issues.

Praveen Gupta: ‘Bright New World’ – what made you write this book for children?

Cindy Forde: I wrote a book for children because I believe the stories we tell our children and how we educate the rising generation is key to creating a brighter future. Einstein famously said, we cannot solve our problems with the same thinking that created them. Even though our ecological systems teeter on the brink of collapse, threatening the stability of our global economy and society, most national curriculums are based on the industrial revolution, the system at the root of these problems. A model based on endless growth when we have finite resources, that fuels climate change, extinction, and almost unprecedented inequalities in wealth within and between countries and people. We must urgently re-design education.

There has probably never been a greater opportunity for transformation to a brighter future for humanity than now, nor the urgency to seize this been more acute.

In the midst of so much ecological breakdown and despair, there is much more than hope, there is a clear road map to a safer, kinder word. If we learn to read that map, to step out of powerlessness, bewilderment and anxiety and orient ourselves in new directions of thought and action, we can all be part of shaping a brighter future.

I wrote ‘Bright New World’ to give children, their families, and teachers the tools to read this map and to be part of building new pathways for humanity.

PG: Climate Crisis makes us all anxious. Particularly the children – who will be our inheritors. Is that why you opted to explain the social, political, and environmental issues facing the planet and how we got to this point?

CF: Yes, absolutely. To have hope and to enable children, all people, to realise their own ability to be part of co-creating the world they want, it is vital to understand how we got to this point and that most of the blocks in our way out of this crisis are social and political.

Most of the solutions, or mitigation, to our major global problems already exist. Earth still retains the resilience and abundance to support the human family and all her other life forms in harmonious co-existence. She is damaged but can regenerate. What must change for this to happen is how we think.

Anxiety can be caused by a sense of powerlessness, of things being out of our control, that nothing is being, or can be done. Instead of fear and anxiety, I asked myself, what if we changed the story for our young people and enabled them to see this as one of the most exciting times to be alive? System change begins with how we teach our children to think. What if the stories we tell start to draw new maps, to equip the rising generation to navigate themselves safely through innovation, social and political change, towards a world with a future?

PG: Would you call it a holistic view – as you choose to go beyond climate change?

CF: Climate breakdown is a symptom of our wider systems crisis. It is a by-product of how our economic and social systems have evolved over centuries of colonisation and industrialisation and cannot be tackled as an isolated issue. Earth is an interconnected web of life, just like our bodies, what happens in one part of the web can have a huge, often unforeseen, impact on another. The solutions must be systemic, holistic.

By inviting children to step into a not-too-distant future where these solutions have been able to take effect, they have the opportunity see what is possible. To visit a world where we collaborate with nature and our natural systems to create thriving cities, wild spaces, oceans; where we use our incredible technological abilities to enhance and support the genius of the natural word; where we have reengineered our systemic issues that currently cause the greatest problems, such as energy, food, travel, economics, how treat and educate girls, to become the biggest part of the solution.

PG: What are the key messages for young people?

CF: That they can be part of creating a brighter world.

Throughout the book, children are asked questions about their own ideas for how to do this. At the end of the book there is list of 10 simple things they can do to use their own power to make change. Some of these are practical lifestyle actions like what we eat, how we travel, how much stuff we consume. Others are about having self-belief, using your creativity, your voice to ask for change. I summarise this as Care. Share. Dare.

Care for Earth, collaborate and dare to think differently about the future you can create.

I frame this in a real-world context that shows that the disaster that we are facing is causing much awakening to the short-sighted folly of ‘endless growth at any cost’. Around the world people are rising up with innovation both in how we do and make things and in how we think. This evolution in mindset is the greatest key to change. The book showcases brilliant young activists at the forefront of this transition and the innovations they are developing at a local and global level, to demonstrate this change is real and already well underway.

The catastrophic imbalance in our planet is mirrored by the catastrophic imbalance in voices in national and international decision making. Decisions that affect our survival as a species are being taken predominantly by a single interest group, the old guard powerbase of the industrial global north. These voices tend to come in an older, white male package.

PG: How important is educating girls so as to take an equal place in society?

CF: I dedicate a section to this called ‘Voices for Girls’. It shows that educating women is one of the leading ways of mitigating climate and ecological breakdown, as demonstrated by the research of Project Drawdown and Population Matters among many other world leading organisation. When girls are educated, they have more control over their reproductive systems and choose to have fewer, or no children. As David Attenborough said, “All our environmental problems become easier to solve with fewer people, and harder – and ultimately impossible, to solve with more people.”

And it is not just population numbers. The catastrophic imbalance in our planet is mirrored by the catastrophic imbalance in voices in national and international decision making. Decisions that affect our survival as a species are being taken predominantly by a single interest group, the old guard powerbase of the industrial global north. These voices tend to come in an older, white male package. The outcome of this monocultural world view is, as with all monocultural ecosystems, unsustainability, and collapse. We have a fight on our hands to change this, as it is a fight against an entrenched status quo reinforced by billion-dollar corporate interests, that lobby governments and pay politicians across the globe.

Educating girls is a vital part of this fight to enable women around the world to mobilise, recognise their own value and take full part in decision making. Including the holistic, collaborative ‘feminine’ world view, and many men also hold this, as opposed to the current dominant model of relentless competition and extraction to extinction is crucial to our survival. So, educating boys to understand the value of woman and girls is also essential.

PG: Women are the ones most impacted by the Climate Crisis, how can their voices be heard? Why are they poorly represented in leadership roles at the likes of the COP?

CF: As outlined, in my previous answer, this is a deeply systemic issue. The current power structures have been put in place by and to maintain a patriarchy. The domination and exploitation of nature in many ways mirrors the domination and exploitation of women. Even in 2021 the British government saw no issue in sending an all-male delegation, at decision maker level, to the COP26 negotiations, even when challenged hard on this by influential women globally. When women in countries where we have considerably more franchise face this kind of political erasure, the devastating level of exclusion faced by women in more overtly discriminatory societies operates like a deadly bog.

Exclusion of women is hard baked into the extant model of colonisation and exploitation of countries, people, nature that has led us to the brink of extinction. Our dominant myths and cultural narratives have been shaped to support this world view and the myth making industry has only grown more powerful as media oligarchs consolidate their influence over the news, to an extent film, digital and social media. The collaborative, ‘feminine,’ natural systems world view does not support the vast profiteering for the elite at the top of the current dominator paradigm that has driven our society for so long. It is, therefore, a worldview that must be repressed, silenced, discredited.

Many men who also hold this world view are also excluded and discredited accordingly. Orchestrated violence, corruption, obscene lobbying, for example by the fossil fuel industry, is all at horrifyingly well-funded play to hold this system in place, and as it now implodes this becomes more extreme and vicious, as evidenced by the petro-state wars now reaching the level of nuclear threat, and the terrifying backlash again women’s rights, in the devastating decision of Roe vs Wade. It takes great courage, collaboration, and commitment to systemic change to get marginalised voices heard. This involves the mobilisation of influence in the diplomatic, corporate, and political sphere such as COPs, campaigning, collaboration and amplification of work and message through well organised, focused global networks of mutual support. It also takes significant funding.

Exclusion of women is hard baked into the extant model of colonisation and exploitation of countries, people, nature that has led us to the brink of extinction. Our dominant myths and cultural narratives have been shaped to support this world view and the myth making industry has only grown more powerful as media oligarchs consolidate their influence over the news, to an extent film, digital and social media.

PG: What needs to be done to ensure a key role for indigenous people and women from Global South?

CF: As outlined, in my previous answer, we need to build strong, cross global networks to influence and campaign. Where people who have power and resources understand how vital it is to include the voices of indigenous people and women from the global south, they must use it. Our time to achieve the meaningful dialogues, listening and action essential to changing our trajectory is extremely short now. We must mobilise in effective and coordinated ways to have an impact at places like COP, which are riddled with corporate interest and have a track record of failure. So, we must also build alternative platforms for global governance where voices from the global south, indigenous people, and women are built in as core constituencies.

I am on the Steering Committee of She Changes Climate https://www.shechangesclimate.org whose aim is to spearhead women’s participation in climate negotiations working in global collaboration. I also support the work of https://www.foundationearth.co, currently incubated by Climate 2025 https://www.climate2025.org to support the emergence of global governance of our biosphere.

PG: Any plans for translating the book into other major global languages?

CF: Absolutely, the rights have already been acquired by a German publishing group, and other international rights are under discussion. I would obviously like to see ‘Bright New World’ in all major languages so its message can reach children and their families in all countries of our beautiful, shared planet.

PG: May this brilliant vision for a ‘Bright New World’ become a reality soonest, Cindy!

https://illuminem.com/illuminemvoices/a9c523b0-82f3-4268-a8df-26b86fafa023

September 23, 2022

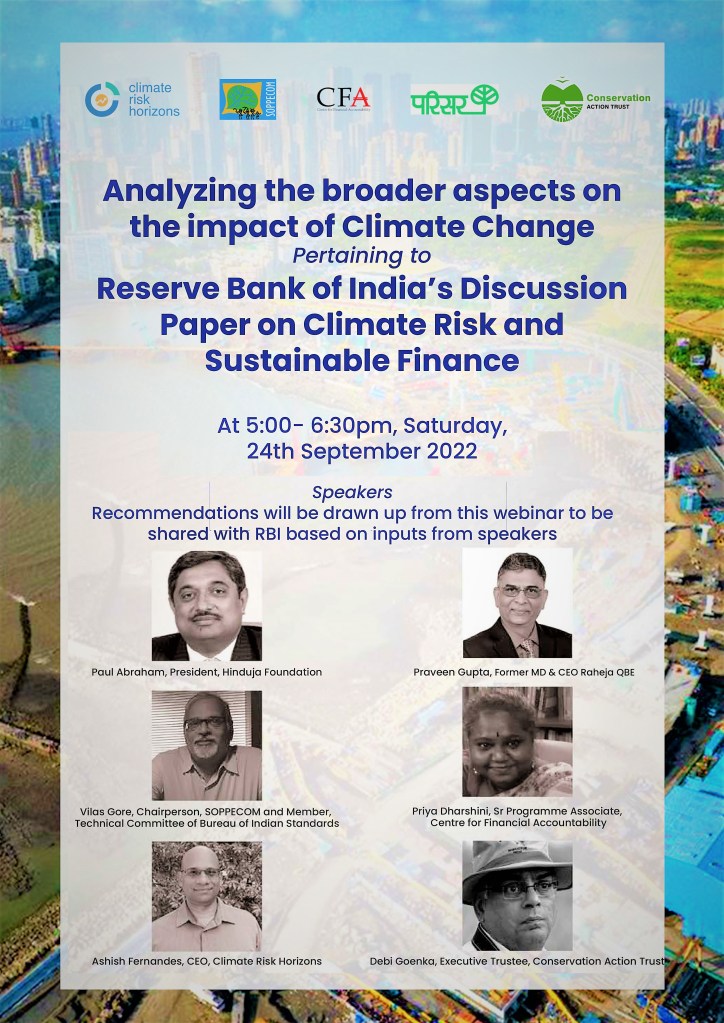

My response to the Reserve Bank of India consultation on Climate Change.

Major Wall Street banks have threatened to leave United Nations climate envoy Mark Carney’s financial alliance over legal risks, according to the Financial Times. So in these flip flop times, from COP26 when everyone rushed to follow him as he played the pied piper – to COP27 – when the biggest of fossil fuel financiers are reportedly ready to abandon GFANZ and jump the ship.

World Bank President David Malpass came under heavy criticism earlier this week, according to Reuters, after he declined to say whether he accepts the scientific consensus on global warming, rekindling concerns about the bank’s lack of a deadline to stop funding fossil fuels. After dodging questions on climate, Malpass told CNN ‘I’m not a denier’.

The scrutiny is on and will get more intense. Not just for banks but all financial institutions. The systemic risk that they pose collectively will only get exacerbated by the systemic nature of climate risk. It disregards geographical or political boundaries; who emits how much GHG; intergenerational implications; and ironically the Global South ends up paying a disproportionate price.

“RBI’s waking up to Environment risk or climate change is a most welcome move, even if the initiative is perhaps a decade too late”, says Dr. V. Raghunathan – renowned author, former banker and an expert on behavioural finance. “But of course, better late than never”. Perhaps it’s also time for RBI and other financial services regulators “to close hands, given the many cross pollination” between various sectors, as Raghunathan puts it.

I draw in some world-wide good practices. Needless to mention, more than the implications of Climate Change on balance sheets of financial institutions, it is the adverse impact of the money pipeline on environment and society that really matters. RBI’s solo performance is too late in the day. It is time for a concerted rapid action.

However, it does not stop here. There is hope in the form the ‘Bridgetown Agenda’ – Barbados’ PM Mia Mottley’s efforts towards building a global coalition to make financial system fit for climate action. Designed to reform the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), institutions set-up at the end of World War II and still dominated by the US and Europe.

http://www.thediversityblog.com

Praveen Gupta: What drew you towards nature and conservation?

Mehreen Khaleel: I have always found solace in nature. I believe it were my parents who were more inclined towards nature and that’s why i find my peace in it. I remember the excitement on my mother’s face whenever she would see a new bird. That was something I missed the most while pursuing my higher studies. But very fortunately, I have had mentors who would encourage to spend some time watching birds on campus. It not only kept me occupied but helped me develop interest in nature and conservation. Very luckily, I could pursue my interests and now I am trying to sow the same seed of conservation in many young minds. The passion which many of our students show is infectious, and I think that keeps me going.

PG: What did you have in mind when you created the Wildlife Research and Conservation Foundation (WRCF)?

MK: During my PhD research, I realised Kashmir’s wild flora and fauna is less studied. General awareness about wildlife in Kashmir was lagging among the younger generation. Unfortunately the traditional environmental knowledge wasn’t given much importance and maybe that was the reason behind this lag. When we started WRCF, we wanted to start a conversation about wildlife of Kashmir, and bring in ideas from the locals. We are a team of dedicated researchers who use scientific knowledge to explore, understand and tackle various issues related to wildlife conservation.

When we started WRCF, we wanted to start a conversation about wildlife of Kashmir, and bring in ideas from the locals. We are a team of dedicated researchers who use scientific knowledge to explore, understand and tackle various issues related to wildlife conservation.

PG: Which animals are most affected by the Human Wildlife Conflict? Is any of it the focus area for WRCF?

MK: In Kashmir it’s the Asiatic Black Bear which has been affected by the Human Wildlife Conflict (HWC). There could be many reasons to it, be it the shift in agricultural practices to cash crops, unregulated garbage management in fringe zones, seemingly increase in the number of bear population etc. WRCF has been trying to understand the dynamics of this conflict scientifically. We have been focusing on mitigating HWC with the appropriate use of technology. We have been in constant consultation with the local stakeholders as we address this issue.

PG: What is the impact of Climate Change in the Himalayan region – visible & invisible?

MK: I remember seeing snow clad Mahadev peak in Srinagar hold its snow till the next winter, which nowadays looks naked as July sets in. It’s disheartening to find such abrupt changes in just very short span of time. Reports of new tropical species of birds and insects is a hint to the wise that “Not all is well in the Himalaya”. Many of us would not be bothered by Climate Change but for an ecologically sensitive place like Kashmir these things matter a lot.

There are too many things which at the inception can be attributed to the Climate Crisis and need immediate ponder. Every year during summers, more than a dozen places witness flash floods, erratic rains. The four seasons (Spring, summer, autumn and winter) which Kashmir was known for, have no longer a clear demarcation. We have seen winters getting warmer with none or very less snow. There is a substantial shift in the phenology of native flowering species in response to climate change.

The four seasons (Spring, summer, autumn and winter) which Kashmir was known for, have no longer a clear demarcation. We have seen winters getting warmer with none or very less snow. There is a substantial shift in the phenology of native flowering species in response to climate change.

PG: Any specific learning from your work: ‘Distribution & feeding ecology of Himalayan gray langur’?

MK: Himalayan gray langur is the least studied high-altitude primate. Not much was known about its ecology and distribution from Kashmir. Previously it was known to occur in Dachigam National Park, but my work establishes its presence in a wider range. They were found in the mountainous protected areas of Kashmir (Kazinag NP, Wangath-Naranag CR, Tral-Shikargah CR, Rajparian WLS, Overa WLS) preferring an elevation range of 1600-3000m. This work served as baseline for various scientific studies and management policies towards the conservation of this high-altitude primate. I also tried to understand the feeding ecology of these primates in seasonal habitats of Kashmir Himalaya. They mostly depend on tree bark, seeds of native tree species found in Kashmir forests.

PG: Do smaller animals, birds, insects and the flora also get your attention?

MK: Yes of course. WRCF has started research projects pertaining to smaller animals, such as Kashmir Flying Squirrel, monitoring local and migratory bird populations. We have already worked on the floral diversity in one of the protected areas of Kashmir, and are expecting a publication on it sometime soon. Last year, in collaboration with WWF-India, we conducted a Wetland monitoring of Odonate survey. We are the first organisation from Kashmir which started the moth week and butterfly month citizen science surveys in partnership with National Moth week and Big Butterfly Month initiatives respectively.

PG: Any thoughts on how to popularise nature conservation and biodiversity protection with the masses?

MK: We have been trying to work out some very conventional models such as use of audio-visual in conducting lecture workshops, nature camps. Mass awareness on social media engages more people at the same time and has turned out to be more effective as well. Since our focus is on the people living in the fringe zones, we have conducted these programs in local languages. Benefits of using local language is that people can easily relate and they can come up with better ways and suggestions about biodiversity protection.

PG: Don’t you think women from Global South should play a much bigger role in environmental matters in the likes of COP27?

MK: I definitely believe that women should play a much bigger role in environmental matters. The likes of COP27 should recognise and encourage such women leaders who would be a source of inspiration for many.

PG: Your thoughts on the role of indigenous people as stewards of nature?

MK: I believe indigenous people have the best knowledge for nurturing biodiversity. They have been the stewards of nature but we have failed to acknowledge their efforts. They have mastered coexistence with nature. Be it agricultural practices, use of natural resources, or dealing with human-wildlife interactions, indigenous people have had the best of practices. This knowledge should be transferred to their younger generations. But somehow this flow has been hampered due to modernisation.

PG: Many thanks for these wonderful insights, Mehreen! My best wishes to you and the team.

The Journal, Chartered Insurance Institute: September 9, 2022

https://thejournal.cii.co.uk/2022/09/09/calm-storm

Delighted to co-author this think piece with the brilliant Zaneta Sedilekova. London based biodiversity and climate risk lawyer. she is the Founding Managing Director of Climate Law Lab Ltd.

We analyse the role that climate liability risk can play in shaping the insurance industry. We look at the main trends in climate litigation against corporates, and its impact on the insurance jargon, wordings and investment outlook. We conclude with some practical suggestions on how climate liability risk can be mitigated on both underwriting and portfolio levels.

Zaneta’s work entails strong focus on risks and opportunities climate and biodiversity crises present to the financial system as well as individual decision-makers. “Most importantly”, as she puts it “I help clients turn these risks into opportunities for their business and wider stakeholders”.

“If we don’t do everything right, that “near to two degrees” will actually be nearer three degrees Celsius, which is five or six degrees Fahrenheit, which is a world where civilizations won’t be able to function in the ways we’re used to them functioning. That civilizational breakdown – a political and human phenomenon, not a scientific one – could come sooner; we don’t know where the civilizational red lines are, only that we’re close”. Warns ecologist and activist Bill McKibben. That would surely redline much of what insurers do!

Very dark times

“We face dark times. Very dark times. All of us… What is coming is especially difficult for those under 40 or 50 years old. They have never experienced this level of adversity that is hitting their ways of life, homeland, communities, and all they take for granted… Closing eyes and a belief that somehow, we can ignore what is fast overwhelming us are simply not options. Highlights Nik Gowing – Founder & Co-Author, Thinking the Unthinkable.

UK-based litigation funders have amassed record war chests to finance the growing interest in class action law suits, according to a new study by RPC. Litigation funders’ assets jumped 11% last year to hit £2.2bn, almost double the £1.3bn that had been built up in 2017/18 and a more than ten-fold increase over the past decade… This is a game changer for GC, Companies. Boards and Law Firms and is not filing anywhere but up.

“I approve of the idea of class action law firms and litigation funding as they do something towards creating equality of arms which is critical to the Rule of Law”. Observes the renowned Prof Paul Watchman.

Insurers with fossil fuel fixation, affinity for biodiversity destroyers and purveyors of pollution – wouldn’t be taking their loss reserves and all the attendant greed of executive rem and board rewards for granted too long. If only they start following what lies in store. A lip service to NetZero Insurers Alliance (NZIA) is a farce and only hastens the encounter with the “very dark times’’.

“Nature merely sends warnings, then consequences… no judgements. The four Horsemen of our impending Apocalypse – ignorance, arrogance, avarice and apathy – are in full gallop today”. Thank you Bittu Sahgal, you couldn’t be louder and clearer!

For those seriously wishing to follow what next, please do track Zaneta’s work. The rest might as well enjoy the calm before the storm!

Praveen Gupta: What got you interested in Climate Change?

Robina Abuya: I trained in climate change (MSc) from Heriot-Watt University, U.K. Beyond that, I have practiced for over 10 years in various capacities at different institutions in the listed thematic areas of climate change. I got interested in climate change during the late 2000’s when Africa and Kenya in particular were facing challenges due to rising impacts and risks of climate change. After completing my undergraduate studies in Biology, I registered for post-graduation in climate change. I was fortunate enough that the commonwealth identified me for sponsorship. During that time, there was no concrete syllabus and specific studies in climate change – especially on policy, adaptation and mitigation.

These roles sometimes put women at risk, but they have over time learnt to adapt and mitigate, so they have vast knowledge on traditional adaptation and even mitigation approaches which they can share with a larger audience.

PG: Don’t you think more women from Global South need to be inducted into global climate leadership, including the COP?

RA: Yes, more women from the Global South should be inducted into global climate leadership, because:

- Women form a high percentage of vulnerable groups, facing multiple vulnerabilities due to various circumstances and risks.

- They interact more with the natural systems and, therefore, any risks due to climate change impact them substantially.

- The various cultural set up and roles played by women in the communities they come from. These roles sometimes put women at risk, but they have over time learnt to adapt and mitigate, so they have vast knowledge on traditional adaptation and even mitigation approaches which they can share with a larger audience.

- Women’s voices need to be heard because they have first-hand experience and, therefore, applicable solutions to some of the risks posed by climate change.

- Leadership of women at that higher level will give confidence to the vulnerable groups because those who understand their plight would be representing them.

PG: How do you think a more expansive role for women would make the desired difference to the Climate agenda?

RA: Women will be able to incorporate practical climate actions. With a visible leadership presence of women, this will give confidence to especially those at the grass-roots that their voices would be heard and incorporated into the various policy initiatives.

Women will be able to incorporate practical climate actions. With a visible leadership presence of women, this may give confidence to especially those at the grass-roots that their voices would be heard and incorporated into the various policy initiatives.

Not only would women be not looked at as a vulnerable population, but will be also recognised as a people that are able to offer solutions and contribute policy mechanisms. This will enable them to relate better with the policy decisions and translate the actions better at implementation level.

The expanded role of women will also mean that they are able to demand for better approaches, mechanisms, compensation etc.

PG: Do you expect to continue your Climate related passion in your new role at the Red Cross?

RA: Yes, my profession is in climate change and environment. I endeavor to continue pursuing this at various lengths and in my new role.

PG: Many thanks, Robina. My best wishes in all your endeavours.