My article published by Margaretta Colangelo on the LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/what-longevity-could-mean-health-life-insurers-view-colangelo/?trackingId=jIETes6DT6meVd8xdtD%2F0w%3D%3D

“If you ever feel inspired to write a short article about what longevity could mean for health and life insurers let me know.” Coming from Margaretta Colangelo this was some motivation!

So, I started with exploring my thoughts from a presentation to young actuaries. During lunch time, at this event, one of the participants asked me what would I do if I were to live that long? I wasn’t prepared but recall mumbling something to do with reading all the great classics, listening to all the fantastic music ever created and travel.

My rumination also took me to a cyber insurance event that I once ran in Singapore. And I did wonder whether a rejuvenated human or on his/ her way to cyborg-hood would tantamount to a Theseus’ paradox?

COVID-19 suddenly ports you into a new normal. With mother nature pushing back the father greed, this would not be last of a zoonotic manifestation. Would one really want to keep living through such extended inequitable times? Is there light at the end of this dark tunnel – leading us humanity duly uplifted?

Would that make space travel more compelling – with the possibility of abandoning the only home we have for a more flexi existence and infinite possibilities that Mr. Bezos envisions for his great grandchildren’s great grandchildren? Thereby not having to worry about CO2 or Methane emissions? The extractive pillaging and biodiversity loss?

And yes, there could be someone amongst us who may live all of 300 years!

Many thanks, Margaretta!

Praveen Gupta: Insurers tend to be lagging behind on the climate agenda. A recent ShareAction finding shows, the investment side seems to be performing better than the underwriting. Is this something to do with remuneration practices?

Frederic Barge: Although executive remuneration is not the sole driver for change, it does play a relevant role. Many corporations have established their purpose over the last decade. In line with the societal concerns, corporations have phrased their “reason d’etre” and their role in society. Their purpose statement is clearly focused on the non-financial contribution to society on the long-term. Looking at executive remuneration most of the purpose elements have disappeared. The vast majority of executive remuneration at corporations is linked to short-term financial performance, and this is often not contributing to the long-term value creation for the corporation’s stakeholders (including shareholders). This apparent gap between purpose and pay is in our view limiting or slowing down the transition to a sustainable economy.

We at Reward Value Foundation, strongly believe that the gap between purpose and pay needs to be closed. This requires changing the time horizon of pay, as well as redefining corporate success. The latter means that corporate success is defined by measuring the impact of the corporation on society from a financial, environmental, and social perspective. Extending the incentive structure, even beyond the active period of the executive, will positively affect the time orientation of the executive and potentially support the focus on innovative and R&D driven investments. Such investments are dearly needed to support the transition to a sustainable and inclusive economy.

Insurers as investment managers are more focused on incorporating ESG factors in their investment philosophy. Also, external regulation is demanding a firm commitment from investors to drive sustainable finance. The developments in the EU with the Green New Deal are a clear example of regulatory pressure on investors. In the underwriting business this awareness is currently less visible, although the impact of climate change will have significant effects on the insurance business. Looking at executive pay policies at many insurance companies; remuneration of executives is still fully or almost fully linked to financial performance criteria. A change in remuneration design may be supportive in changing behaviour of executives and their organisations.

PG: There is a serious shortage of climate literate board members. How do you resolve that?

FB: Russell Reynolds and the UN Global Compact have made an analysis of the inclusion of ESG knowledge in board and executive vacancies. It turned out that only 4% of the vacancies had some ESG requirements in the hiring process. So, looking at that study, it becomes apparent that already in the hiring process, ESG-related knowledge, and experience (including climate) should be a key component of sought expertise. Diversity of experience (as well as diversity broadly) will add to the effectiveness of boards. Secondly, ESG knowledge can and should be shared in education programmes both for existing leaders as well as for future leaders. As Reward Value we will contribute to such curriculum additions with our research on executive remuneration and our behavioural experimental research. By including ESG into executive remuneration, and more importantly in strategy, strengthening the internal expertise and obtain access to external advice will become of paramount importance.

PG: Do you see corporations talk long-term and act short-term? How do you fix this misalignment to ensure a sustainable outcome?

FB: As I mentioned, corporate purpose statements are mainly long-term oriented, while executive pay is much more short-term oriented. This misalignment needs to be addressed for several reasons. First of all, intrinsically well-motivated leaders should not be hindered by incentives that take their attention away from long-term sustainable value creation. It is key that extrinsic motivation through incentives is enforcing leaders to execute in accordance with their intrinsic motivation to do good. Secondly, incentive agreements are a contract between managers and their company, whereby shareholders are to vote on the remuneration policy. This means that a remuneration plan mainly focused on short-term financial performance also tells you something about the shareholder view on long-term sustainable value creation.

Shareholders should support alignment of pay to purpose and therewith demonstrate their own commitment to a sustainable, regenerative, and inclusive economy. Thirdly, extending incentives and maybe even extending nomination periods, may also support the willingness of leaders to invest in R&D and innovation. Dealing with today’s challenges to the environment and society requires corporations to move away from short-term earnings realization towards long-term sustainable value creation. In summary, time orientation needs change among the different market parties.

PG: Some sustainability practitioners in Europe suspect significant greenwash under the guise of green new deal. Shareholder versus stakeholder remains an unfinished agenda?

FB: I believe that with respect to environmental and especially climate related topics, we are not completely there yet. But corporations are more and more aware that change will happen. I am positive that corporations learn to think not only in risks but also in opportunities with respect to climate change. Regulation remains important, especially from a reporting and disclosure perspective, but making sure that regulation is stimulating behavioural change rather than stimulating a compliance “tick-the-box” mentality or even worse an evasion mentality. To be effective, corporate behaviour towards sustainability must be based on corporate intrinsic motivation and conviction, and not on compliant reactive response to regulatory requirements. With respect societal topics and especially diversity and inequality, the progress is much slower and also gets much less attention. Yet both climate and inequality are disruptive to society and deserve immediate action.

Your second question on shareholder versus stakeholder is more difficult to predict. The future of the current business model of corporations with (concentrated) shareholders is dependent on the success of the business and investment community to deal with the stakeholder well-being including that of the shareholders. The increased interest in different structures like B-corps and co-operative structures with shared ownership among a multitude of stakeholders is a promising development but needs a significant overhaul of legislation in jurisdictions across the globe and therefore will most probably progress more slowly. Ignoring inequality will accelerate the desire for new corporate structures. This in itself is another reason for shareholders to take societal issues very seriously and stimulate businesses to better serve its stakeholders.

PG: In absence of desired behavioural change do you prescribe an element of claw-back?

FB: Payment schemes that reward executives for realised investment returns but do not penalise negative returns, encourage excessive risk-taking. Two commonly used measures to combat the potential forms of fraud and exercise risk-taking are: Bonus caps and claw-back measures. Bonus caps create a ceiling for the variable compensation, and claw-back measures make it possible to reclaim bonusses that were awarded in the past. A disadvantage to the bonus cap is that it can potentially cause a drop in effort after the maximum bonus is reached. This is less the case for the claw-back measures. The effectiveness of claw back measures, however, is still limited. On the one hand, it requires a strong board of directors that is willing to act when needed and expected. Often such difficult decisions remain not taken. Secondly, from a legal perspective it is often difficult to execute on claw-back policies. Legislative amendments are needed to make claw-back an effective tool and therewith become effective in influencing executive behaviour.

PG: How can companies strive to become sustainable contributors to societal long-term value creation, when their chief executives are remunerated on short-term goals?

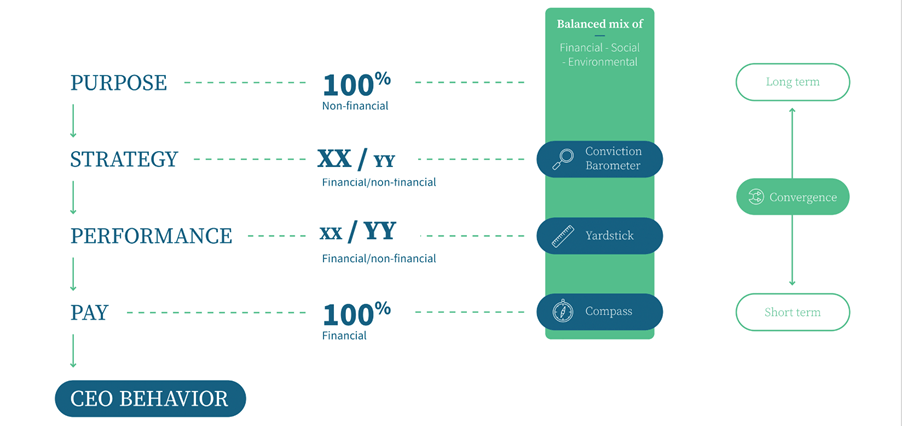

FB: Whereas purpose has evolved taking the challenges of today and tomorrow into account, pay has remained unchanged except for the level of pay. This gap has to be addressed. What analysis is needed?

In the assumption that pay reflects a performance[1], the first question to ask is what performance should be remunerated? This requires a renewed definition of corporate success, which should entail the impact of the company on society both from a financial perspective and from a non-financial perspective (environment and social). The success of an organisation should be measured according to financial, environmental, and social impact. Ideally, the environmental and social impact is monetized to allow an overall assessment in the same currency with the financial impact. The approach of the Impact Weighted Accounts Initiative of the Harvard University is a strong tool for this.

Next to a quantitative analysis based on impact measurement, a qualitative assessment of corporate activities is needed, whereby the materiality of the sustainability strategies of companies is key, as research has also demonstrated that only the material sustainability topics add value on the long-term[2]. Many corporate governance codes require companies to contribute to long-term value creation. Often the definition of long-term is not given. Especially, when pay is structured in shares (as also recommended by Prof. Alex Edmans), it is important to understand when share valuation is a fair reflection of a company’s accounting valuation (both financial and non-financial). As you can see in the picture here above, Reward Value performs research on these three elements of long-term value creation, being quantitative impact analysis (Impact Yardstick), qualitative strategic analysis (conviction barometer) and definition of long-term (convergence).

The subsequent next important analysis to make is whether renewed remuneration design will impact executive and corporate behaviour. According to research, executives at least seem to demonstrate short-term oriented behaviour around vesting moments of incentives.[3] By means of experimental research, Reward Value is exactly examining this question. Our research is on-going, and it is too early to tell whether it will be effective, but the analysis needs to be made before any conclusions, as made in your article by some, can be made.

Finally, renewed executive remuneration also needs renewed corporate governance and strict and mandatory reporting. Moving executive remuneration away from short-term financial coupled with vague non-financial targets to long-term sustainable value creation with transparent mandatory reporting will in our view result in a better alignment of pay with purpose. The experimental research will be able to give more insights in the effectiveness of executive pay in changing corporate behaviour. Executive pay will never be the solution to all but structured well it could be a catalyst for change. From Reward Value Foundation, we invite academics and market parties to participate in and contribute to our research.

PG: There is a significant gap between what women and men get paid across the rank and file?

FB: Whereas most attention is nowadays given to climate, the other big disrupter in today’s world is inequality. An inclusive society gives equal opportunities to all and does not discriminate on the basis of gender or ethnic diversities. An inclusive society unites people and establishes a social cohesion. In a report published in 2019, ILO demonstrates that diversity leads to better corporate performance.[4] In an extensive literature review performed by Anja Kirsch, the positive effect of gender diverse boards on social and ethical aspects of firm behavior is discussed.[5] Also the Sustainable Development Goals of the UN Global Compact[6] give clear guidelines on diversity and inclusion. I mention just two sub goals:

- SDG 5.5

Ensure women’s full and effective participation and equal opportunities for leadership at all levels of decision making in political, economic and public life. - SDG 10.3

Ensure equal opportunity and reduce inequalities of outcome, including by eliminating discriminatory laws, policies and practices, and promoting appropriate legislation, policies and action in this regard.

PG: My best wishes, Frederic, in your endeavour to bridge executive remuneration with the long-term value creation. The sooner we get there the faster would we transition to a sustainable economy.

[1] Gabaix, Landier, and Sauvagnat (2013), CEO Pay and Firm Size: An update after the crisis. Frydman & Saks (2008), Executive Compensation: A new view from a long-term perspective, 1936 – 2005.

[2] Serafeim, Kahn, and Yoon (2016), Corporate Sustainability: First Evidence on Materiality.

[3] Edmans, Fang, and Lewellen (2017), Equity Vesting and Investment.

[4] ILO (2019), Women in Business and Management: The business case for change.

[5] Kirsch, A. (2018), The gender composition of corporate boards: A review and research agenda.

Praveen Gupta (PG): How do you suggest we address the biodiversity hotspots of the world? Both in terms of containing and regenerating them?

Rhett Butler (RB): I think most people who manage natural resources now understand that efforts to protect nature and biodiversity need to be broader than the strict protected areas approach which dominated conservation in most parts of the world until 20 to 30 years ago. That being said, it seems like recognition of the positive conservation outcomes resulting from other interventions – increasingly known by the clunky term “other effective area-based conservation measures” (OECMs) – has really accelerated over the past decade or so, especially in territories stewarded by Indigenous Peoples and local communities (IPLCs). But it feels like we’re still more in the messaging and commitment phase, rather than the implementation phase. I think that’s partly because of inertia: The protected areas approach is what’s been done for so long and is conceptually easier to understand than a mix of different forms of land use and management. I’m still not entirely convinced that follow-through from some conservation institutions will live up to the declared level of ambition on the inclusivity front.

Even once there is general consensus around the interventions that are effective in achieving conservation goals, the world still needs to secure the political will and financing mechanisms to actually conserve and restore ecosystems. Political will is challenging as long as conservation is viewed as a “special interest” for only a small segment of society. Therefore, one of the key aspects of driving conservation at scale is to make it relevant to everyone. That means highlighting how healthy and productive ecosystems directly underpin human wellbeing. For example, the fact that forests are a source of clean water, generate local and regional rainfall, and reduce ambient air temperature.

Sometimes focusing on only the positives is not enough because people tend to take the status quo for granted. Therefore, we also need to talk about what happens when ecosystems are degraded. For example, replacing a rainforest with a large oil palm plantation can raise local temperatures by several degrees, boost the risk of flooding, worsen erosion, diminish the availability of clean drinking water, and increase rat and mosquito populations. All of these impacts have real costs for local communities.

PG: But what does this mean for the developing world? What climate impacts will affect the frontline and indigenous communities native to the most vulnerable disaster areas?

RB: Ecosystems in the tropics are especially important in terms of carbon storage, biodiversity, and other ecosystem services. And many tropical nations are developing nations, meaning they’ve historically contributed the least to climate change, yet are the ones that are most vulnerable to it. This is even more magnified for frontline IPLCs, which generally have been the most responsible for the persistence of healthy and productive ecosystems, yet often bear the brunt of both climate change and policies that aim to stem it.

The climate impacts on these communities depend on where they live, but in many cases will include reduced food security, increasingly extreme weather events, and shifts in the ecosystems upon which they rely. In low-lying coastal areas, IPLCs will be forced to reckon with rising sea levels, which will worsen storm surges, inundate homes and agriculture, and erode coastlines. In polar regions, IPLC communities are already dealing with the effects of melting permafrost and changes in the availability of fish and game.

These communities are also suffering from the consequences of environmental degradation. For example, fires in places like Borneo, Sumatra, and the Amazon have adverse effects on local peoples’ health. And climate change is expected to exacerbate these fires, making them more common and severe.

While there is growing recognition of the contributions IPLCs have made toward stewarding “wilderness”, some communities could be further disadvantaged by some of the solutions being promoted to address climate change. For example, there is a push to promote biomass energy as a “carbon neutral”, but replacing native forests traditionally managed by communities with industrial plantations is bad for climate and dispossess local peoples of the ecosystems upon which they depend. And, of course, the “fortress conservation” approach common until relatively recently sometimes involved forcing Indigenous communities off their customary lands.

PG: Isn’t a sense of urgency amiss?

RB: To me it feels like the sense of urgency among the general public around climate change has greatly increased in the past couple of years. I think this is the result of the worsening impacts from climate change – especially crazy weather events and disasters – as well as the pandemic. But it doesn’t seem like that sense of urgency has translated into concrete action from governments quite yet beyond making commitments that will ultimately be some other person’s responsibility to turn into reality at some point in the future.

PG: How important is the role of multilateral agencies?

RB: Multilateral institutions have an important role in bringing governments and other entities together around an agenda, establishing frameworks and protocols for taking action, and aggregating funding, among other things. In general, I don’t look to multilaterals for cutting-edge leadership or ideas, but once they are on board, it can generate momentum.

PG: Techies generally believe the current mess was created by technology and will also be solved by it?

RB: I live in Silicon Valley, where there’s widespread belief that there’s a technological fix to everything. Optimism is important of course, but there’s a danger that being overly optimistic lulls some people into a sense of complacency in that there’s less reason for action if one believes there’s a tech solution just around the corner.

Still, technology can be a great tool in supporting efforts to protect the planet. Environmental monitoring, for example, has been transformed by technological advancements to the extent that we no longer have ignorance as an excuse for not taking action on issues like deforestation. We can plainly see where it’s happening and to what extent.

One of the areas I’m most excited about when it comes to technology as it applies to biodiversity is monitoring soundscape ecology with bioacoustics devices. When combined with camera traps and satellite imagery, bioacoustics can paint a much fuller picture of what’s happening within a forest ecologically (I was a co-author of a paper on this topic a couple of years ago). I think environmental DNA also has incredible potential.

Of course, technology can have downsides. At the most basic level, there are the materials that go into things like EV batteries, solar panels, and mobile phones, which often have very significant environmental impacts.

PG: How does one make these initiatives more diverse and inclusive?

RB: One of the problems with some conservation technology is it is not inclusive and does not consider local needs. Some of these products and services are designed to run on a 4G network by people with a lot of training or technological experience. An extreme example was presented to me a few years ago where an organization was pushing an anti-poaching solution that required a team of flight engineers in an office in the United States to control a pricey drone as it flew over parks in Africa. The military overtones aside, this approach was costly and didn’t build in-country capacity or buy-in.

It has been encouraging to see initiatives that focus on providing technology that’s fit for purpose, actually works in the field, and meets people’s needs. For example, IPLCs are using GPS and mobile phones to map their territories as a way to secure or strengthen land tenure. Some communities are using Google Earth, Global Forest Watch, ESRI ArcGIS, or other geospatial tools to monitor their lands for encroachment and illegal activities. And there are even examples of technologies strengthening intergenerational connections between the traditional holders of knowledge – community elders – and kids who have access to things like phones, computers, and the Internet.

Mobile phones have created new channels for communities to collaborate and learn from each other, in some cases allowing once isolated groups to find allies and mobilize broader awareness about their struggles and the challenges they face.

PG: Farmlands and urbanisation continue to rapidly decimate our forests. Do you see an ongoing Zoonotic wave resulting from it?

RB: There’s a growing body of research linking encroachment into forests, disruption of natural ecological processes, the wildlife trade, and livestock management practices to zoonotic diseases. I think Sars-CoV-2 woke a lot of people up and led them to start paying attention to these intersections, which scientists have been warning us about for years. Before COVID-19 of course, there was Ebola, Zika, MERS, SARS, Nipah, and Avian Influenza, just to name a few recent examples.

Hopefully the scale of COVID-19 will keep zoonoses a priority for policy makers and funding agencies. Still, if we carry on with business-as-usual, we should expect more zoonotic pandemics – some researchers have identified the cattle sector in the Amazon as the potential birthplace of the next big new crossover pathogen.

PG: Do you see the rise of investor activism as an effective means to direct the money pipeline towards sustainable outcomes?

RB: If we’ve learned anything from the past 30 years of climate and biodiversity talks it’s that governments are not leading the way in addressing environmental crises. Leadership more often comes from individuals, civil society organizations, and companies. Governments do play an important role, but I wouldn’t say most are at the cutting-edge in terms of big ideas.

Given the scale of the problems we face, it’s going to take an all-hands approach and companies have the resources, power/influence, and ingenuity to develop and implement solutions. Of course, some companies are more aligned with sustainability than others – the business-as-usual interests continue to oppose progress on climate change, deforestation, pollution, and other issues.

One of the mechanisms for driving corporate behavior change is investor activism. It’s been really interesting to see this play out with shareholder activists targeting big oil companies of late.

The opposite approach is divestment, which has dramatically accelerated in the past decade after emerging out of student movements at universities. Many philanthropic foundations have since stopped investing in fossil fuels. And even governments have gotten involved: Norway’s sovereign wealth fund has exited investments in a number of companies linked to deforestation and coal mining, for example.

There’s also been a tidal wave of investment in renewable energy in recent years, which is producing a transition in power generation that’s far outpacing expectations in some countries. And the shift toward electric vehicles has been much faster than I could have imagined just a few years ago. Most of this is happening because people see this as an opportunity to make money, rather than to do good, though doing good is a happy byproduct for most people.

Lastly, I’d add that environmental activism has also played an important role in influencing the conversation. In the late 2000s, Greenpeace was instrumental in driving the emergence of the zero-deforestation movement among companies that produce, trade, and buy commodities associated with deforestation. While companies haven’t yet lived up to their commitments to eliminate deforestation from supply chains, the movement has forced them to become more accountable and laid the groundwork for other developments.

PG: Net Zero has serious implications for greenwashing. Any hope for afforestation resulting from carbon offsets? Can valuing of eco system services bring some sense?

RB: There are high risks of adverse impacts from net zero goals that don’t incorporate safeguards: Net zero without the proper standards leaves huge loopholes for environmental degradation, human rights abuses, and other harms. You mention afforestation for carbon offsets, which has certainly been a problematic area going back to the Kyoto Protocol in 1997. There are plenty of examples under that old framework of carbon credits financing the conversion of natural forests for industrial plantations.

That being said, many decisions are based on economics and if nature doesn’t have a price tag on it, some companies and governments will treat it as having no value. So, it’s important to be able to talk about the economic value of healthy and productive ecosystems. But we have to be sure that everything is on the table when having this conversation. That means measuring the positive economic values of ecosystem services and fully accounting for the costs of business-as-usual, including the underpriced or ignored externalities that currently subsidize sectors like fossil fuels.

On the ecosystem services front, when it comes to forests, most of the focus the past 20-30 years has been on carbon sequestration, but I think that the role these ecosystems play in driving local and regional rainfall will increasingly be a significant part of the equation when assessing their value.

PG: Grateful Rhett for helping my understanding of all these complex linkages at the very heart of a serious existential crisis. Please keep up your great work to ensure we transition safely through these challenging times.

Praveen Gupta: It is ‘billed’ as the ‘whitest’ COP of all?

Alessandra Lehmen: The pandemic and the recession that followed suit posed a significant barrier to emerging countries’ participation. The UK Presidency relaxed quarantine and vaccination requirements and extended access to vaccines to participants, but it was an uncertain and costly process that, in practice, prevented wider participation from Global South delegates. Online participation was possible, but that would require proper access to the internet, something that is not readily available to all emerging countries’ delegates.

PG: Did you see many women leading the events and getting their due place in the sun?

AL: I did. Despite a lack of diversity in certain fora, women are traditionally very active in environmental and climate matters. The same holds true for Environmental and Climate Law, where notable women have been inspirational leaders for decades. One of the panels in which I spoke, for instance, was comprised only of women attorneys.

PG: Were women and youth from the Global South visible and audible?

AL: Yes. Just to give you one notable example, Txai Suruí, a young indigenous leader and the first representative of her people to attend Law school, was the only Brazilian to speak at the opening ceremony.

PG: Oil and gas industry continuing to play a spoilsport?

AL: According to NGO Global Witness, oil and gas industry representatives were the largest group at the summit, surpassing Brazil, which had the largest official delegation. At the level of the negotiations, countries that have been historically blocking measures related to phasing out fossils, such as ending subsidies, have continued to do so. Also, major producers have not adhered to the coal phase-out pledge championed by the UK presidency, but important consumer markets, such as Canada, Poland, and Chile, have done so.

PG: Does the conference first draft shock you?

AL: I see the document as comprehensive, but somewhat watered down in diplomatic language. The US and China’s joint announcement that they will work together on a number of climate-related actions has sparked some cautious optimism as negotiations draw to a close. It will remain to be seen if, before the end of the conference, further progress is made on topics that I see as crucial for keeping the 1.5 degree goal alive, such as fossil subsidies, the Article 6 rulebook, and finance.

Protests are an integral part of COPs, and there were plenty of rather creative manifestations both inside and outside the venue. Perhaps the one that touched me the most was Simon Kofe’s, Tuvalu’s foreign minister, who has filmed his speech from a podium knee-deep in the ocean. It was a stark reminder that the current generation of children could be the last to grow up in the small island state.

PG: Heroic and valiant attempts by protestors, how impactful?

AL: Protests are an integral part of COPs, and there were plenty of rather creative manifestations both inside and outside the venue. Perhaps the one that touched me the most was Simon Kofe’s, Tuvalu’s foreign minister, who has filmed his speech from a podium knee-deep in the ocean. It was a stark reminder that the current generation of children could be the last to grow up in the small island state.

PG: Was it a good idea to have a COP15 (re: biodiversity, at Kunming) ahead and separately of COP26. Deforestation being a critical component, did it receive the deserved attention?

AL: Biodiversity COP15 was aptly dubbed by the media as “the most important COP you have never heard of”. Biodiversity issues are closely intertwined with climate change, particularly in a pandemic: more climate change leads to more habitat loss, which in turn leads to more exposure to pathogens. Deforestation did receive attention at COP26, though: more than 100 countries – including Brazil – pledged to end and reverse deforestation by 2030 and the documents include almost $19.2bn in public and private funds.

I have seen commentators mention that the pledge is limited to illegal deforestation, but the statement makes no such caveat. It remains to be seen if the pledge is interpreted and implemented in a way that is conducive to effective alignment with the 1.5 degree goal.

PG: Is Net Zero a mirage?

AL: I use to say that, although a race to the top of climate ambition is welcome, I am more interested in assessing what concrete, measurable progress a country or a company has to show for by the end of the next fiscal year, rather than in who makes the biggest net zero pledge for 2040 or 2050. I mean, we know where we want to go, now let’s get moving. Also, net zero and carbon neutrality are not synonyms, so we need absolute reductions, as opposed to only relying in compensations, to get there.

PG: Many thanks for these wonderful just in time first-hand insights, Alessandra! Hearty Congratulations for your leadership.

I was honoured to present to the General Association of the German Insurance Industry, earlier today – on behalf of Mr. Gautam Boda, Group Vice Chairman, JB Boda & Co. The GVNW represents the interests of the German insurance industry and advises them in the various areas of insurance cover. Needless to mention, in addressing the Climate Crisis the money pipeline ought to be addressed, too. Insurance is an important component of this pipeline.

Metaphorically speaking the business climate in India is in a state of flux and will only intensify. Going forward the key driver will indeed be #ClimateChange. What makes this a fascinating subject matter is the fact that several inter-related triggers are together driving it into a systemic zone. The ongoing blending of emerging risks is creating a heady concoction. It is thereby nudging risk management to overcome its myopia, self-imposed limitations, reactive methodologies and reliance on the retrospective. Leveraging the emerging systemic risks calls for imagination, adaptive practices and all-round resilience – so as to anticipate new demands of this marketplace and arrive at a win-win outcome. The presentation endeavoured to chart this path.

Praveen Gupta: Do you expect enough women leaders at the COP26?

Maria Alexandra: No, there are not enough women leaders attending the COP26. And whenever they are, they tend to be diminished in the shadow of the white male representation. I often get demotivated or even saddened with the fact that I join climate advocacy negotiations in rooms full of white men. And I remember that I need to get over my temporary feelings, to still be part of the decision-making process. However, the most stringent issue for me regarding COP26 representatives and leadership is not necessarily the gender imbalance, but the lack of correct representation of the world’s nations. This year’s COP not only highlights the utter inequalities amongst the countries, but also the obstacles to the delegations coming from the Global South countries and perhaps most importantly, from the indigenous communities.

PG: Why must we have an equitable representation of women?

MA: In order to ensure a fair (emphasis on fair) decision-making process, both during the planning and implementation phases, we must take into account everyone – as the UN’s agenda itself follows the motto ‘Leave no one behind’. However, most of the times, as the crucial decisions are taken behind closed doors, between mainly male representatives, they do not reflect the voices of those coming from the underprivileged communities – Small Islands Developing States (SIDS) and Least Developed Countries (LDCs). They also do not have the magnitude of voices that the US, the EU and the big ‘actors’ have. Our role, as climate advocates who are privileged enough to assist either the preCOP26 or the COP26 negotiations, must use this privilege to speak up on behalf of those underrepresented or undermined. And this leads me to highlight an eye-opening experience as a delegate to the preCOP26 this year in Milano.

PG: Any first-hand lessons from the Youth4Climate event?

MA: The Youth4Climate summit served as a prelude to the preCOP26, and as a young delegate of Romania, my country of origin, I got a chance to speak up my mind and represent the reality of a country that is often not widely known: the improper educational structure that generates enormous gaps in people’s behaviours and the ‘survival’ mode of my people. When I talk about ‘survival mode’ I talk about people who struggle with poverty, lack of financial means to ensure a decent living, lack of perspectives for their future, working each day simply to provide themselves the basic means of subsistence.

Both at the Youth4Climate and PreCOP26 summits I understood that the reality of my country is often reflected in so many others… and in most of them, the situation is even worse. One of the main topics that we addressed during our preCOP26 negotiations with the world leaders, as youth climate advocates, was the topic of ‘loss and damage’.

The climate crisis has gone, unfortunately, so far that multiple countries from the Global South are fighting its consequences on a daily basis: severe droughts, floods and heavy rains that impact to an enormous extent their agriculture and food production. In short, these countries’ climate change consequences are so severe, that their lives are completely affected by them: no more subsistence means, such as food or clean water and the urgency for displacement has gone extremely high. Amidst all this, these countries are paying for the consequences of a climate crisis that they have neither produced nor triggered. It was actually the big polluting countries, developed nations, that under the Paris Agreement are expected to pay up according to the Rule Book.

At the preCOP26, as youth leaders, we saw the governments standing up and pledging their financial promises to developing nations, SIDS and LDCs. But they continue to be reluctant. I remain hopeful and I am charging myself for some full days at the COP26. I know exactly where I will stand as a woman youth climate advocate, speaking up on behalf of those whose voice was not given the privilege to attend the summit. And that underlines a big problem – the voices that must be heard should be urgently given a fair opportunity to have a seat at the decision-making table.

PG: Best wishes in your efforts towards reinforcing the voices that must be heard and should be urgently given a fair opportunity to have a seat at the decision-making table.

Published in Bimaquest, September 2021

‘Riskier times ahead for the Risk Carrying Business’ – is what lies in store for the business of insurance – unless it acts seriously and urgently on the Climate Crisis front (Bimaquest, September 2021).

‘Despite increasing pledges of action from many nations, governments have not yet made plans to wind down fossil fuel production’, says a UN report. ‘The gap between planned extraction of coal, oil and gas and safe limits remains as large as in 2019’, when the UN first reported on the issue. The UN secretary general, António Guterres, called the disparity “stark”.

A report, produced by the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) and other researchers, found global production of oil and gas is on track to rise over the next two decades, with coal production projected to fall only slightly. “Fossil fuel production set to soar over next decade”. Countries plan to produce around 110% more fossil fuel than would be compatible with a 1.5C temperature rise by the end of this century (Mark Campanale).

Ironically, as Wolfgang Kuhn, CFA highlights: “Insurers say the solution is not to penalise brown investments but create a greater supply of green assets.” And all we have in terms of time, warns renowned climate scientist Michael Mann: the “lag” between halting CO2 emissions and halting the rise in global temperatures may be as little as three to five years.

Businesses, as a rule, do not like being forced to do anything – reminds Brett Ryder of The Economist. They prefer to make voluntary gestures – just enough to keep governments off their backs. Right now they are throwing around promises to cut carbon emissions to “net zero” like confetti… On the one hand the UNEP bares it all but the @UNEP FI initiatives for financial institutions remain toothless.

Peter Bosshard points out a serious disconnect: “of the 5 new Net Zero Insurance Alliance (NZIA) members, only @NN_Group has a strong coal exit policy. #HannoverRe is still covering coal through treaties, and none of the others have taken any steps to pass this low bar”.

‘Offsetting schemes are pure #greenwash so that fossil fuel companies can continue to do what they’ve been doing and make a profit’. Jennifer Morgan of Greenpeace has called for their immediate abolition. All this would not be possible without the money pipeline and the hypocrisy of banks, insurers and asset managers actively involved in this space.

The disconnects, double standards and skullduggery et al make insurers’ case as agents for a green transformation increasingly challenging. Before the existential issues assume a more threatening and irreversible form for them, reputational risks are already in play!

Praveen Gupta: Are there enough women at the COP 26 leadership, in your opinion?

Benedicte Herbout: To be completely transparent, I had not even really checked before you asked me. I just took for granted that it won’t be many, and in fact it is not. I would have been positively surprised if it had been the case though. Fact is, the COP is structured to represent all the parties – a majority of which don’t manage to reach gender equalities in their own countries.

What does comfort me (a little) is that the advisory team seems to be balanced – and in the end, advisors are often listened to. However, while I believe there are gender balance issues in the leadership team of the COP26, what is more problematic to me is the lack of representation of women from low-income countries. Women are suffering the most from climate change, low-income countries will suffer the most from climate change and so women in low-income countries are on the front line. Are they being listened to? I doubt it – we don’t even listen to the (wealthier) (male) scientists.

In addition to low-income countries’ women, we miss the youth too. They/we (I’m 27) are living and will live the consequences of years of inactions. We need to adapt and fight to avoid the worst and adaptation strategies need to take into considerations the views of the most affected. I fear the COPs are just meetings where the elite talk a lot – empty words otherwise we would have seen the difference.

Maybe, maybe, if the leadership of COPs were made of people who can’t fly away from climate change, things would change, action would follow. So I am bit unsure about to answer in the end. I am frustrated that one still asks this question – it should be given, so we can focus our energy on listening to who will suffer the most and act consequently.

PG: Why is it critical to have their voice?

BH: What is critical to me is not only this representation of youth, women, low-income countries balance. What is critical is that so many of us don’t really understand climate change. I mean the scientific mechanisms behind it. There is no climate education curriculum that tells you how all this works and why and that hinders any action. One can’t solve a problem if one does not understand it.

That is why I am cycling to the COP26 and facilitate Climate Fresk workshop on the way. While many ask whether it is also to make a point as a solo traveler woman, I actually never thought of it that way. I just want to popularise climate science and make people aware that we in Europe are highly privileged, and blind to consequences that climate change have on all of us, affecting some more. Listening to science is the first step to act, which then makes clear that we need to act all together. For the youth, for the low-income people, for the women.

PG: What are you eventually trying to achieve?

BH: My goal? Re-unite people from different political and economic backgrounds behind science, so that climate change can be treated with a common scientific understanding and solutions pragmatically debated and implemented.

PG: Happy cycling and may you realise your dream, Benedicte!

Honoured to chair a very stimulating panel discussion, earlier this evening. Delighted that BIMTECH considered evolving the Natural Catastrophe forum into a #ClimateChange theme and the esteemed panel was in concurrence to call it what has now become a full blown #ClimateCrisis! Hoping that this will metamorphose into a standalone event, soonest.

Coming from Reunion Island & living in Mauritius, Aurélie is intensely sensitive to the fact that: “We are going to see a lot more serious disasters striking us in the future. We have to keep in mind that rising sea levels will have huge impacts on tourism, a pillar of our islands’ economies. It is, therefore, imperative to reinforce the existing legal framework all together with the adaptation projects on the ground. We must not forget that not only material damages can occur but that down the line people’s lives are at stake.”

Women…again!

”Last year, the British COP26 host team found itself in trouble for not addressing gender imbalances in politics when announcing an all-man team. Women involved were to be working at a more junior level on subsections of the negotiations. This created a wave of indignation and more than 400 women in international leadership denounced it”, tells me Aurélie . #SheChangesClimate stood for inclusivity, transparency and accountability to the COP negotiations on the climate crisis, campaigning for a #5050Vision, reminds the jurist. Even though (little) measures to rectify the situation have been taken, the whole story brings shadows on the ability of the UK to truly stand up to the spirit and challenges of climate change, which, in return, doesn’t sound very appealing nor hopeful for the outcome of the COP, she believes.

The ugly truth

This faux pas might sound like an epiphenomenon, but it appears unfortunately as a lieu commun, and even more so as a painful truth. The lack of representation of women in the climate negotiations is paradoxical and unfair, particularly when one considers the importance of women on the ground. Indeed, women are change agents: they identify what must be done and can take necessary measures to make it happen. Moreover, they are the first to be directly and seriously affected by climate change and they are far more at risk. This message from Aurélie is a reinforcement of what the other women leaders have been saying again and again.

The IUCN study “Gender-based violence and environment linkages: the violence of inequality” from 2020 shows how the degradation of nature has a complex linkage with gender-based violence, she highlights. Their integration in the climate processes represents chances of success and will ensure fair decision making. Despite these facts and arguments, we notice that women are still not represented enough in high-level circles. During the 2019 COP25, only 21% of the 196 heads of delegations were women. Yet, diversity is the way forward if we’re ought to achieve the climate targets, let alone to stay truthful the Paris Agreement’s spirit! One legitimately may ask: is justice so blind? Well…Not quite, believes Aurélie.

What does the legal framework do about it?

Indeed, the actual legal framework is not bare on gender considerations. Women participation and representation in the negotiations process is a concern since 2001 (see namely decisions 36/CP.7, 1/CP.16, 23/CP.18 of the COP). Although rather poorly equipped on the matter, The Paris Agreement (PA) recognises the need for gender equality and empowerment of women under the scope of human rights in its Preamble. Articles 7 and 11, as well as the Katowice Climate Package also contain references to capacity-building and gender-responsive adaptation action, she opines.

In fact, a cornerstone has been established under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) when the Lima Work Programme on Gender (LWPG) was established and extended by the COP (see Decision 18/CP.20 & Decision 1/CP.21), shortly followed by the first gender action plan (GAP, see decision 21/CP.22). Considering the need to address the challenge, COP25 adopted the enhanced five-year LWPG and its GAP (see Decision 3/CP.25), which aims “to advance knowledge and understanding of gender-responsive climate action and its coherent mainstreaming in the implementation of the UNFCCC” at all levels, reminds Aurélie.

The UNFCCC Secretariat publishes an annual report on gender and climate change to assist the Parties in tracking their progress. The last report unveils a slight improvement, asserting that “the representation of women in Party delegations increased by 9 per cent and among heads and deputy heads of Party delegations by 12 per cent”. Unfortunately, it also points out that “Despite these increases, women remain the minority, representing 49 per cent of Party delegates and 39 per cent of heads and deputy heads of Party delegations.” She alludes to the Report by the secretariat (FCCC/CP/2021/4, 20 August 2021, p.8. available online).

Human Rights Based Approach, next?

While the data shows that the situation is not as gloomy as it seems to be, however, perseverance and determination are more than needed to become structural. This is the real challenge. Of course, actions can be taken to ensure strict equality, but I believe we must address the problem in a sensible manner and see the big picture. This is the reason why a human rights-based approach (HRBA) perfectly makes sense and should be at the very core of all law-making processes in environmental matters. HRBA allows decision making to consider a broad variety of interests while keeping an alert eye on vulnerable groups that need specific attention, is her prescription. If everything is interconnected, inclusivity must be the pathway to achieve climate goals, SDG’s, and human rights. Aurélie concludes with a quote from one of her favourite authors – Victor Hugo – “To put everything in balance is good, to put everything in harmony is better.” Such pearls have got to come from a woman leader!